A TIMELINE FOR

THE PLANET click for Home Page

Modern humans

appear

Opinions differ about when modern humans emerged. Around 200 ky seems about right these days,

though this is a good deal earlier than used to be thought.

Taking

over the planet

The Genetic contribution The Rise of Culture Weaving & the Venus

figurines language & symbolic thought the Neanderthals

It was during the worst glacial period. Our immediate predecessors are believed to

have been a fairly insignificant species, Homo.

antecessor.

Part of the

reason why our arrival time is uncertain is that, to begin with, we made very

little impact. For possibly 150,000 years we continued to live

the primitive lifestyle of our forebears.

Then, as we’ll see later, we exploded on to the scene and changed the

world.

It’s thought that we began like this.

Towards the start of the cold period, a small group of

H. antecessor may have been isolated

in a small haven in

Geneticists believe that there was a time when there

were only some 10,000 of us, and that our total population remained that small

for “a long time” (whatever they may mean by that). And this period seems as good a candidate for

such a ‘bottleneck’ as any. The reason

they believe this is that the variation in human DNA is extraordinarily

small. A single group of chimps has

wider DNA variation than the entire human race.

But that’s not all.

The DNA variation of the world’s non-African population is much smaller

still. I’ve read that a single African

village has more variation in its DNA than that of the entire rest of the

world. We’ll discuss why this might be

later.

We should mention the

‘Aquatic ape’ theory. It’s a

highly controversial theory that evokes strong passions on both sides. It suggests that we may have had to take to

the water at some point, and that to survive we had to become

semi-aquatic. The only evidence for the

theory lies in certain features of modern humans. But some of these are quite striking – like

our exceptional swimming ability, or the fact that we can safely give birth

underwater. Even today, our babies are

born with the right instincts and capabilities to cope. There’s also the layer of fat that we have

under our skin. This is ‘buoyant’ white fat, not insulating brown fat. Many aquatic animals have this, but no other

ape does. There are other striking

features too.

Many scientists reject the idea

completely. No hard evidence, you see. But I’ve always been a bit

of a water-baby and I fancy it. If there

was an aquatic phase then again this seems as good a time as any for it to have

happened. We must remember that Darwin

found the folk of Tierra del Fuego living naked in temperatures around freezing. They were quite happy to swim in water with

ice chunks floating in it!

The Neanderthals appear to have emerged in Europe from

Homo erectus, at about the same time

as we evolved in Africa from H.

antecessor. Although anatomically we

were significantly different, we lived very similar lifestyles for a long

time. This is rather odd actually, but

it does seem to be so. The Neanderthals

had icy

How was this possible?

We did have an opportunity to sample each others’ toolkits during the

last interglacial, some 120,000 years ago.

We expanded northwards and the Neanderthals expanded southwards. And the common ground was Israel. Note the weasel words though. I’m not clear whether we met face to face, or

whether the see-sawing weather led to us taking turns to occupy the same set of

caves. Either way we would each have

been introduced to the other’s tools and other artefacts. There’s usually only one ‘right’ way to make

a tool. Modern flint knappers have

‘reverse engineered’ many ancient toolmaking techniques, purely by

experiment. Both we and the Neanderthals

were certainly smart enough to do the same (more).

We may have reached southeast Asia. But we still didn’t make much impact. The Neanderthals remained in charge in Europe

and Homo erectus in Asia. Then the cold returned with a vengeance and

we had to retreat back to Africa.

Taking over the planet

Modern humans were not the first to expand out of

Africa and to take over other parts of the planet. This prize goes to the mighty hunter, Homo erectus, nearly 2 million years ago – or possibly to the even

earlier australopithecines, see the

same link. And, between ice ages, folk

have been living as far north as

As we’ve just seen, modern humans had a go 120,000

years ago. But it didn’t work out.

Then, about 45,000 years ago, the climate warmed again

and a small group of us had another go.

I say ‘small group’, because that would explain why the DNA of the rest

of the world is so much more restricted than that of the African

population. (We may have done it in two

waves, 60 and 40 odd thousand years ago.

Reports differ.)

This time we swept all before us. We drove Homo

erectus from southeast Asia, and we drove the Neanderthals from

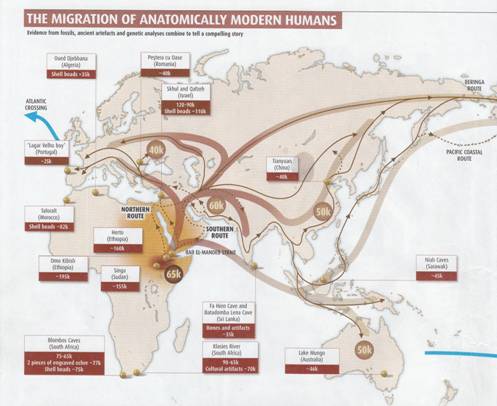

But an article in New Scientist (27.10.07)

gives what seems to be the latest theory, as this map shows. The broad arrows indicate general movements,

as indicated by genetic studies. The

narrow ones suggest possible actual routes.

The article doesn’t explain the blue arrows, depicting

Apparently there were two routes north from our

possible refuge. One was through the

Sahara desert. There were various times

when the Sahara was humid and inviting.

So if the timing was right, this could have been an attractive

route. We mentioned earlier our

primitive ancestors, the Australopithecines. They are thought to have wandered aimlessly

northwards, right out of

The second route is across the mouth of the

Colonising south-east Asia and even Australia was

fairly easy, because again, all folk had to do was to follow the coast. We appear to have reached Australia within

some ten thousand years of leaving Africa.

We will have had to do a bit of seafaring, though it’s not clear how

much because sea levels were much lower at that time. H.

erectus was already there of course.

But I’ve not seen how much of a problem they were for us.

But expanding northwards was more of a problem. It seems to have taken another then thousand

years for us modern humans to follow the Australopithecines into eastern

Europe, for example. Not only was it

colder for us, and we had to invent warm clothes. But the Neanderthals were already there, and

pretty well as advanced as us. I’ve read

that it took about 10,000 years to supplant them. During that time we seem to have co-existed,

with a certain amount of interaction. Did

we interbreed? Opinions differ.

America was an even bigger problem and, as we’ve seen,

it took a lot longer still.

Why were we so much more successful this time? Theories abound. Warm clothes are nowhere near enough to

explain it. Our brains seem to have

remained exactly the same size although, as we discuss elsewhere,

intelligence and brain size don’t go together nearly as closely as you

might think. Some scientists argue that our

‘small group’ acquired a mutation that improved the way our brains were wired

up.

The Genetic contribution

As we’ve said, the broad arrows on the map reflect

what genetic evidence is telling us.

Genetic evidence has had a chequered history.

The theory goes thus.

Organisms’ genomes are continually acquiring minor mutations. There’s no ‘method’ to this. They appear in a

thoroughly disorganised and random fashion.

Some prove beneficial, and help the organism in its fight for

survival. Even if the benefit is small,

beneficial mutations become more common.

Other mutations of course are harmful, so naturally they become

rarer.

But the vast majority of these mutations have no

practical effect at all. They just

accumulate, at a roughly constant rate, for maybe hundreds of millions of

years. Inter-breeding ensures that all

the members of a particular species carry the same selection of useless

mutations. (That’s the theory anyway.) But when a species splits into two, this

interbreeding stops, and each group starts to collect its own selection.

So geneticists can count (maybe ‘estimate’ is a better

word) the number of mutations that each branch has acquired since the

split. This enables them to put a number

to how long ago the split was.

The trouble is that the geneticists made the same

mistake that so many other scientists make, to their eventual cost. As we’ll discuss shortly, they made an

assumption that they didn’t realise that were making. Scientist often do this. The high and mighty cosmologists are some of

the worst culprits, as other cosmologists keep telling them (more). These

assumptions can all too easily be wrong.

As a long-term student of the Earth story, I’ve seen scientists having

to back-track many times.

The geneticists assumed that there was some mystical

genetic clock that controls the rate that any genome acquired these mutations –

and that this clock has run at a constant rate over the entire period of

interest. As we’ve said when we’ve met

this problem elsewhere, in a sense they could do no other. If that’s all the evidence you’ve got then

you have to do your best with it. The

trouble comes when you actually start to believe it. And this is exactly what so many scientists

do.

When the geneticists started getting dates that

conflicted with other evidence, they announced that they were right, and that

the other findings were wrong. (This may

have been a long time ago, but we chroniclers suffer pain when scientists make

stupid and arrogant claims – and we have long memories!)

But then (the shame of it!) the geneticists started

getting different answers according to which part of the same genome they

studied. They eventually got round to

doing what we engineers have always done (big money and even lives can be at

stake in our work). They started

checking out their assumptions properly before deciding how much weight to give

them.

In brief, they are now much more careful, and much

less arrogant. As a result their results

are taken considerably more seriously.

The genetic evidence indicates a rapid expansion along

the coast into India, a slower one along the eastern Asia coast ending up at

the Bering Strait, and a slower one still through the heart of Asia. Finally we have the slowest one of all, along

the southern

It took a very long time for us to get across from

Asia to America. But we discuss this in

greater detail under sail.

But that’s not the end of the story. Apparently genetic evidence, taken from

modern populations, can estimate the rate of population expansion at different

times and in different places. It sounds

a bit unlikely to us uninitiated, but it has to do with the famous

mitochondrial DNA. The mitochondrial DNA

evidence points to a population explosion between 70 and 80 ky ago, “perhaps in

a small source region in

We have to point out that, plausible though this

theory is, the proponents of rival theories dispute it.

And here’s another twist. Apparently between 150 and 70 ky ago, the

climate in

The rise of culture

We suggested earlier the theory that a genetic

mutation triggered our great exodus. But

some scientists believe that a step change in culture is all the explanation

you need, and they could well be right.

There have been pretty major step changes in culture since then, and

nobody is explaining these in terms of any mutations. The ancient Britons, for example, took to the

heady new Roman civilisation like ducks to water. That is to say, the tribal leaders did. I suspect

that the ordinary folk lost out badly.

The Industrial revolution

brought huge changes in its wake, even more quickly.

Not all scientists agree that our change in culture

was all that sudden anyway, e.g. Kate Wong in Scientific American June 05.

‘Sudden’ developments do have a habit of evaporating as more evidence

comes in.

In the case of culture the answer appears to depend on

where you are looking. In

We also mustn’t forget the old adage “absence of

evidence is not evidence of absence”. We

can’t prove that certain ancestors were doing this or that until we find

evidence. But we certainly can’t say

that they were not actually doing it long before – particularly if, like fire

or personal adornment, it would not readily leave evidence. For example, there are wall paintings aplenty

in Europe, where they were done in caves.

In Africa hardly any have been found so far, because they were done on

rocky outcrops. Should we say that wall

painting was a European invention?

Certainly not.

It also depends, as so often, on ‘exactly what you

mean by …’.

The strict definition of ‘culture’ is the ability to

learn from your mates, and many of the higher animals do this. I’ve read that first-time chimpanzee mothers

have to learn how to suckle their young from more experienced mothers. Is this culture? The normal test for culture is that different

unconnected groups do things differently from each other. They may all make tools for extracting

termites from their nests. But they use

different techniques for fashioning them.

It would be fascinating to know how different groups of chimps teach new

mothers how to suckle.

But now we’re using ‘culture’ to mean something much

more sophisticated. I suspect that

different scientists mean different things by it too.

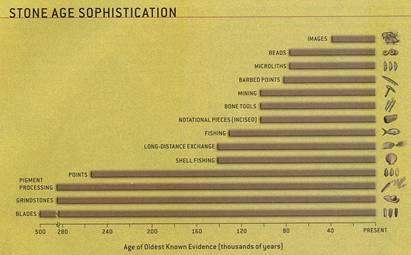

This diagram comes from the Scientific American article.

Wong has chosen to interpret ‘culture’ as beginning with stone ‘blades’

½ million years ago. This is pretty  arbitrary. The first stone tools so far found are

actually 2½ million years old (more). But she had to start somewhere.

arbitrary. The first stone tools so far found are

actually 2½ million years old (more). But she had to start somewhere.

Wong’s blades were found in

We also discuss, at the same link, the exquisite

throwing spears made near Heidelberg at around the same time. If sharp blades are an indication of culture

then surely these spears are too.

Neither of these folk were ‘us’. I don’t know about the

The diagram is not very clear. But it shows a progression of new inventions,

from ½ million years ago to 40 thousand.

One of the first, at around 850 ky, is ‘pigment processing’. This is normally interpreted as implying

personal adornment, a cultural activity if ever there was one.

Then

comes a long list of technological inventions, such as fishing, working with

bone, making barbed spear and arrow heads, and so on. But there’s also long-distance trade, at 140

ky. You can’t imagine this happening

without a fairly sophisticated culture.

And ‘incised notational pieces’ have been found at 100 ky, which are

taken to imply counting or even trade and accounting.

Then

comes a long list of technological inventions, such as fishing, working with

bone, making barbed spear and arrow heads, and so on. But there’s also long-distance trade, at 140

ky. You can’t imagine this happening

without a fairly sophisticated culture.

And ‘incised notational pieces’ have been found at 100 ky, which are

taken to imply counting or even trade and accounting.

Beads appear, in

Finally come ‘images’ at some 40 ky (more). These early images were pretty crude,

and I’m not sure how many scientists regard

‘culture’ as starting quite as early as this.

In any case, what they should be saying perhaps is ‘advanced culture’ or

something, to make it clear that they understand how much they are leaving out.

Weaving and the Venus

figurines

I’ve read that folk were already into advanced weaving

techniques by 28 thousand years ago. No

woven material has survived, not surprisingly.

The evidence comes mainly from archaeological sites in the Czech

Republic. Apparently they show clear

evidence of sophisticated weaving and plaiting techniques, netmaking, plaiting

and coiling baskets, dating back to this time.

There are also artefacts such as the ‘Venus

figurines’, of which this is the most famous.

It’s the Venus of Willendorf  found,

surprise surprise near Willendorf in Austria.

Its date is uncertain, except that each re-dating seems to put it

older. The latest I’ve seen is 30-25

ky. This one fits neatly into the palm

of the hand.

found,

surprise surprise near Willendorf in Austria.

Its date is uncertain, except that each re-dating seems to put it

older. The latest I’ve seen is 30-25

ky. This one fits neatly into the palm

of the hand.

The sexual importance of the figurines is very

obvious, and for a long time any other possible significance was

overlooked. It was originally assumed,

for example, that they were carved by men.

But I’ve read a report

(New Scientist

Not only that, but they display detailed knowledge of

weaving and plaiting techniques that the article suggests only an experienced

weaver and plaiter would be aware of.

If this is true, then it implies that the figurines were actually

carved, not by men at all, but by women.

(Either that, or the men did the weaving!) If this becomes accepted then it will set the

cat among the pigeons in a big way.

One could doubt all this of course. A carver who is truly dedicated to his art

might well wish to capture the finest detail of his subject. And he will presumably have had a mate to

consult over anything that puzzled him.

They may not yet have had ‘language’ as we currently know it. But I don’t see how we can possibly doubt

that they could communicate pretty well.

What is indisputable, it seems, is that the folk of

the time were heavily into vegetable materials for making clothing and other

things.

Language and ‘symbolic’ thought

With advanced culture is held to have come symbolic

thought. Symbolic thought is a somewhat

hazy concept to most of us. Scientists

believe that it emerged with advanced culture.

Between them they constituted a huge advance on anything that went

before. Note the weasel words ‘is held

to have’ and ‘scientists believe’.

There’s no evidence that the two were linked. Neither could there be. And some scientists theorise that symbolic

thought emerged as soon as we, Homo

sapiens, appeared at least 150 thousand years before. That is to say symbolic thought evolved as

soon as our brains could cope with it.

There’s no sign of cultural activities anything like as early as

that. Well there is actually. The Boxgrove folk seem to have been making

handaxes ‘for show’ hundreds of thousands of years earlier still (more).

But assuming the mainstream view is right, then a much

more complex language had to develop at the same time. And fairly quickly at that. This

is reckoned to be the point at which ‘communication’ turns into language

proper. When you have mastered symbolic

thought, you suddenly need to be able to say a wide range of new things. So you need a much more sophisticated method

of communication to enable you to say them.

For the first time, you need a fully-fledged language as we understand the

notion today.

If symbolic thought came with advanced culture, then

it’s clear that we are talking about a purely cultural breakthrough. There seems to have been no difference

whatever between the folk who lived before and after it emerged. This needn’t surprise us too much. There was no difference between the folk who

lived before and after writing was invented, or advanced civilisations emerged

such as the Egyptians or the Greeks. And

it may surprise the young, but those of us who were alive before the computer

age are exactly the same as those who grew up after.

However for my part, I’m with Wong in believing that

the whole process was actually a good deal more gradual than many scientists

currently believe. Indeed, I would

probably go even further than Wong (more). ‘Man the mighty hunter’ (more), of well over a million years ago,

wiped the sabre-toothed tiger from the face of

Richard Cowen (of History

of Life fame) has a different reason for thinking that language started

early. He reckons that it had to do with

the taming of fire by the ‘mighty hunters’.

And this seems to have been by the same folk, some 1½ million years

ago.

Were these guys into the cruder elements of symbolic thought? I would have thought so. But it probably depends on ‘exactly what you

mean by’ – symbolic thought.

To make the sounds that we use for speech these days,

you also need mechanical adaptations to the larynx and breathing

equipment. Our predecessors don’t seem

to have had these. Did they evolve under

pressure of the need to make a wider range of sounds? Or did we simply exploit what we acquired for

some other reason? My guess, like so

much else in science is – a bit of both.

The Neanderthals

It’s interesting that the Neanderthals developed an

advanced culture pretty well at the same time as us. It wasn’t quite the same, but it was

remarkably similar. We strung animal

teeth into necklaces, and so did they.

But we bored holes in the teeth, whereas they cut notches to help the

‘string’ to get a grip. We made

pendants, bone tools and knives. And so

did they. But the techniques used were  different.

different.

The Neanderthal culture is called Châtelperronian,

whereas ours is called Aurignacian.

There are arguments over whether the Neanderthals copied their culture

from us. But I’ve read a report in Scientific American (April 2000) that

says that in fact the Neanderthals got there first. However it would be more than my life was

worth to suggest that we copied from them!

I’ve read conflicting reports about how much better

our Aurignacian toolkit was

The ‘Cro-Magnon’ folk who took over Europe were only a

small outpost of the H. sapiens

population. But they seem to have left far more than their fair share of

evidence about how they lived. This

could be because they had to live in caves.

And caves are very good for preserving evidence. There seems little doubt that the Cro-Magnons

had the edge on the Neanderthals in almost every area of endeavour. This picture of a Cro-Magnon is by Zdanek

Burian.

The Cro-Magnons had richer and more sophisticated art

and tools. And they used stone-tipped

arrows and spears. The Neanderthals’

Mousterian tools were designed for woodworking.

But the Aurignacian kit (more) that

the Cro-Magnons brought with them enabled them also to work with bone, antler

and stone.

© C B Pease December 07