A

TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

The rise of

humans

How like animals are we?

We are genetically very similar indeed to modern

chimpanzees. It seems that our two DNAs

differ by less than 1½%.

what

is the difference between us and animals? when did our line split off?

So

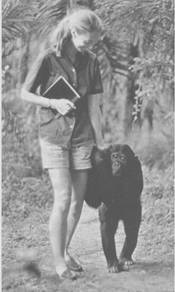

how come that we’ve been told that animals are just machines? It seems that, back in the 1920s, scientists

made a “hideous philosophical error” (Colin Tudge, New Scientist, 11.3.95).

They decided that animals were just machines, and persuaded the rest of

us to agree. It wasn’t until Jane

Goodall arrived on the scene, around 1960, that this nonsense began to be

questioned.

So

how come that we’ve been told that animals are just machines? It seems that, back in the 1920s, scientists

made a “hideous philosophical error” (Colin Tudge, New Scientist, 11.3.95).

They decided that animals were just machines, and persuaded the rest of

us to agree. It wasn’t until Jane

Goodall arrived on the scene, around 1960, that this nonsense began to be

questioned.

Perhaps we shouldn’t lay all the blame on the

scientists. Before the coming of steam,

it suited us very well to regard our draught animals as little more than

machines. Even today it suits us to

regard our food animals in a similar light.

One of the capabilities that animals share with us,

I’m sure, is enjoyment. When we see

seagulls wheeling around in the up draughts against the cliffs, how can we

doubt that they are doing it for fun?

There’s no food for them up there.

Of course they are also honing their skills. But that’s why we do things for fun – to hone

our skills. Many of the skills that we

acquire in this way are pretty useless to us now. But the principle must be the same.

[Click for a more complete story, including more about

scientists’ “philosophical error”.]

So what is the difference

between us and animals?

Well for what it’s worth this is my take on it.

I reckon that we are animals, with an extra layer of

computing power added.

Our basic brains are very much the same as that of

animals – at least the higher ones. That

is becoming clearer every day. And it’s

from this basic brain that we get the capabilities that animals have. For the higher animals at least, this

certainly includes a certain amount of thinking, culture, toolmaking, and other

things that we used to regard as uniquely human – including enjoyment!

But then we went on gradually to develop a major

upgrade. We acquired an extra layer of

more sophisticated brain, tacked on top.

This enables us to take these capabilities so much further than any

animal as to be out of sight.

That’s the best I can do.

When did our line split

off?

It depends on who you ask. Let’s say between 5 and 7 million years ago,

possibly somewhere around

The common ancestor of both us and the chimpanzees

seems to have been a primate called Ardipithecus.

The origins of walking

Until

very recently, the debate over walking seemed to concentrate on some

Until

very recently, the debate over walking seemed to concentrate on some

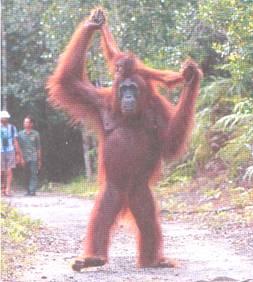

But now it seems that the early ancestors, of all apes,

had long been into “hand assisted bipedalism”.

They walked along the slender outer branches of trees, holding on to

other branches for security, to get at the best fruits. They also used these branches as a bridge to

the next tree.

The ancestors of modern orang-utans, like this guy,

kept the ability. And so did our

ancestors. But those of other apes lost

it.

So when climate change forced our ancestors down from

the trees, we were already reasonably well prepared for it.

However our early ancestors’ walking ability was

hampered by the need also to be good at tree climbing. It was not until the arrival of ‘the mightily

hunter’, Homo

erectus, that we became true people of the plains.

[Click for a more complete story, including the first hard

evidence.]

Our first serious ancestors

The

folk who split off from Ardipithecus,

and ended up with us, are called hominids.

We know very little about the early hominids. The evidence simply isn’t

there. (There’s a fashion to rechristen

us all hominins. The new name seems to mean exactly the same

as the old. I’ve seen no convincing

justification for the change. So I’m

sticking with hominids for now.)

The

folk who split off from Ardipithecus,

and ended up with us, are called hominids.

We know very little about the early hominids. The evidence simply isn’t

there. (There’s a fashion to rechristen

us all hominins. The new name seems to mean exactly the same

as the old. I’ve seen no convincing

justification for the change. So I’m

sticking with hominids for now.)

But we do know about the Australopithecines (nothing to do with

Over that that time they developed quite a lot, though they still had “the brains of apes

but the bodies of men”. Their brain size

was in fact very similar to that of the smartest modern chimpanzees, at say 450 cc odd. They were smaller than us, at around 65-110

lb. And they presumably lived in social groups,

like their cousins the chimpanzees.

However a cache of robust skulls has been examined. It suggests that, unlike chimpanzees, male

robusts were on average 17% bigger than females. This implies a social grouping much more like

modern gorillas, in which a dominant male maintains a harem of females – for as

long as he can keep rival males away.

[Click for a more complete story, including a new theory about the

wanderings of the Australopithecines.]

The first stone tools

And by 2½ million years ago these ‘brains of apes’

were making stone tools (more). Perhaps this shouldn’t surprise us too

much. Many of the great apes make simple

twig tools. And they use stones to

hammer with. If you hammer too hard,

the stone breaks. And you find yourself

with a useful sharp edge. Maybe the

surprise is that none of the great apes discovered this.

[For a more complete story, including our ancestors’

main toolkits, click on the link above.]

The first primitive humans

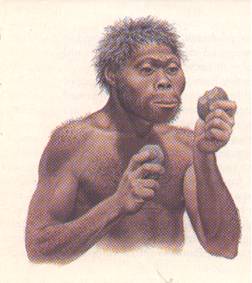

We

have another step change now, to the first primitive humans the Homos – H. habilis. H. habilis counts as a primitive human

because they had brains half as large again (around 600 cc), smaller jaws and

teeth than the Australopithecines. Their skulls are much more like ours

too. These early Homos were small, about

the same size as the Australopithecines.

We

have another step change now, to the first primitive humans the Homos – H. habilis. H. habilis counts as a primitive human

because they had brains half as large again (around 600 cc), smaller jaws and

teeth than the Australopithecines. Their skulls are much more like ours

too. These early Homos were small, about

the same size as the Australopithecines.

They had a pretty comprehensive toolkit, the Oldowan

toolkit (for more, click on stone-tools link above), which served them well for

over a million years.

It’s not clear that they were much good as hunters,

though their small teeth and large brains suggest that they had a pretty

nutritious and easy-to-eat diet.

You can make a pretty good living from scavenging, as

many modern animals show. And we can

reasonably expect these guys to have done a better job than scavenging animals

because they were smarter.

The importance of brain size

The bigger your brain is, the smarter you are,

right? As a general rule, sure. But don’t be fooled. We modern have a wide range of different

brain sizes, and scientists are beginning to discover that a large brain

doesn’t necessarily go with high intelligence.

For example, there’s the celebrated French intellectual Anatole France. He was obviously very intelligent. But his brain was only 2/3rds the normal size

– about equal to Homo erectus (who

we’re about to come on to).

And when they try to assess how intelligent our early

ancestors were, the scientists haven’t always had a big enough sample to take

these vagaries into account.

Brain size is certainly hugely important but, as we

keep saying, don’t expect things to be simple in this game.

[Click for a more complete story, including birds and ‘The

Hobbit’.

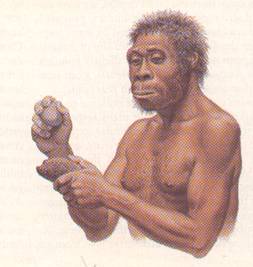

The arrival of the mighty hunter

The next great step occurred around 2-1½ million years

ago, with the appearance of Homo erectus. Opinions differ about how large his brain

was. This shouldn’t surprise us. We’ve just discussed how variable brain sizes

can be, and the anthropologists have very few H. erectus skulls to measure.

In any case, H. erectus’s

brain seems to have grown considerably during his million-year year reign. I’m going for 750 cc, or about half the size

of ours.

During

the reign of H. erectus, the big cats

and the last of the Australopithecenes

vanished. And man the mighty hunter took

over the whole of East Africa.

During

the reign of H. erectus, the big cats

and the last of the Australopithecenes

vanished. And man the mighty hunter took

over the whole of East Africa.

H. erectus

were true people of the plains. We’ve talked

about our earlier ancestors being able to walk.

But there’s all the difference in the world between being ‘able to walk’

and being ‘a true walker – and runner’.

And H. erectus was the latter.

They had sacrificed their tree-climbing skills, by acquiring

long straight legs and arms (no doubt there were many other adaptations as

well). As a result they were no better

climbers than we are.

They had to shrink their pelvises until they were no

bigger than ours are. And their babies

were born as helpless as ours are, with the brain continuing to grow

considerably after birth, just as ours do.

It’s difficult to imagine them getting away with this burden on their

resources, unless they had a complex and stable social structure. So we have to imagine them living reasonably

settled lives in, say, village-sized communities.

H. erectus

inherited the ancient Oldowan toolkit from their Homo Habilis ancestors. But

at some point they invented a brand new one, the Acheulian toolkit (more).

Acheulian tools are more difficult to make than Oldowan tools, and they

need more strength. But they are much

more effective too. And the kit

contained a wider range of tools. Most

of them appear to be for butchering.

It’s striking that H.

erectus’s Acheulian tools are far better made than they need to be to do

the job (more). The scientists are quite clear that these

tools must have had ‘symbolic’ purposes of some kind. So these ‘primitive’ folk, with brains not

much more than half the size of ours, had the maturity and the imagination to

appreciate exquisite workmanship. This

doesn’t surprise me. It may not surprise

you. But it will horrify some

scientists. These folk had developed a

lifestyle that gave them both the incentive and the leisure to develop their

skills to the full. It has been

suggested that ‘impressing the girlfriend’ was one of the reasons for making

these superb tools. I like it!

Some

scientists reckon that the dawn of language may have been about then. This is far earlier than most scientists

believe. But we’ll never know for

sure. Of course it all depends on what

you mean by ‘language’. You can have a

pretty primitive ‘method of communication’ and still get a lot of knowledge

across (More on language.)

There’s also a theory that H. erectus was into fire and

cooking. The theory has to do with “how

did these folk power their huge brains?”

It seems that cooking allows you to expend less energy digesting both

your meat and your veg., leaving more for the brain.

There is evidence for fire

this early, but it’s very controversial.

However scientists regularly tell each other that “absence of evidence

is not evidence of absence”. How long

would you expect the evidence of a camp fire to last if it wasn’t in a

protected cave or something?

It’s not clear when H. erectus finally died out. It could have been as recently as 50,000

years ago.

[Click for a more

complete story, including a new theory about where H. erectus came from.]

The spear throwers

From Homo

erectus on, the picture becomes very confusing. I’ve read that they eventually died out

leaving no issue, but I have to say that I find this difficult to believe. Somewhere within the confusion there must be

a link.

The next big development seems to be the spear-makers

of Heidelberg, Homo heidelbergensis,

about ½ million years ago. They left a cache of exquisite throwing spears. A modern javelin maker would be proud to have

made them. Around that time too (I

think) animal shoulder blades start appearing – with spear holes in them.

Shortly afterwards, around 400,000 years ago, come

‘the Butchers of Boxgrove’, who appear to be the same people. Very few human remains have been found, so we

can’t be sure. The Boxgrove site is all

that remains of quite a large area on the south coast of England. These guys were clearly living the life of

Riley. They had plenty of meat, and

time on their hands to make masses of perfectly good hand axes – and then throw

them away unused – just like the Homo

erectus folk a million years before them.

they weren’t quite good enough to impress their girlfriends. If you don’t like that explanation, then feel

free to think of a better one!

But these guys aren’t our ancestors. The cold returned, and they spawned the

Neanderthals (more).

I’ve read that we Homo

sapiens, and the spear folk H.

heidelbergensis, both stem from a small earlier group called Homo antecessor. They don’t appear to have made much of an

impact in Africa, where they must have evolved. Most of the information about them has been

gleaned from a site in Spain.

[Click for a more

complete story, including the Flint Tool factory.

[Click for the next

phase, modern humans.]

© C B Pease, February 08