A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

Our ancestors’

toolkits

We used to be told that only Man could make

tools. We now know that that’s

nonsense. Here is a picture of a chimp

stone hammer, used for cracking  panda

nuts. It comes from the Max Plank

Institute. It’s not a very good picture,

but the text says that the stone shows deep wear. It has clearly been used a lot.

panda

nuts. It comes from the Max Plank

Institute. It’s not a very good picture,

but the text says that the stone shows deep wear. It has clearly been used a lot.

Toolkits: Oldowan Acheulean Mousterian Aurignacian

As far as I know, no animal breaks stones up to make

tools. But both great apes and birds

strip leaves from twigs, so that they can poke them down into termites’ nests

and such.

What makes us unique is not that we make tools, but

that we make such good ones.

The Stone Age

Before we go any further, we ought to offer a word of

warning. We call the last 2 million years

or so ‘the Stone Age’, because stone implements are all that we find in the

digs. But that doesn’t mean that folk

weren’t using a wide range of other materials besides. In fact I think we’re entitled to assume that

they were. As our ancestors got smarter,

they will have developed more sophisticated uses for hides, bones, sinews,

plants, wood and you-name-it. But we’ll

never know because the evidence will all have rotted away long ago.

Take string, for example. The experimental archaeologists tell us that

many fast-growing bushes like bramble (the blackberry bush) can be used to make

excellent

cordage. They produce long, and very

strong, sinewy strands that can be extracted (with difficulty) from the

prickles and fleshy parts – and twisted together to make string or even

rope. When did our ancestors discover

this? We will never know. But we certainly can’t assume that they

weren’t using string and rope, just because we don’t find any in the digs.

excellent

cordage. They produce long, and very

strong, sinewy strands that can be extracted (with difficulty) from the

prickles and fleshy parts – and twisted together to make string or even

rope. When did our ancestors discover

this? We will never know. But we certainly can’t assume that they

weren’t using string and rope, just because we don’t find any in the digs.

However the key to exploiting all these materials is

something to cut with. And until a few

thousand years ago, that meant stone.

The earliest

proper stone tools

The trick that our ancestors learned was to ‘knap’ a

stone to produce a sharp edge. This

picture comes from ‘Earth Story’ by Lamb & Sington. To you and me, it may look like any old piece

of broken stone. But an experienced

flint knapper will tell you at once that it has been ‘worked’ to produce a

crude cutting edge. It was made about 2½

million years ago by folk who have been described as ‘brains of apes, bodies of

men’ (more).

The Oldowan toolkit

Fairly soon afterwards came the first proper toolkit,

the Oldowan toolkit. It must have been

effective, because Oldowan technology lasted for nearly a  million

years, from some 2½ to around 1½ million years ago.

million

years, from some 2½ to around 1½ million years ago.

It’s not clear how much of the Oldowan kit was

invented by the ‘ape men’, because very soon afterwards came the first ‘Homo’s (see above link), whose brains

were half as large again.

The technology is called ‘Oldowan’ because the first

specimens were found by  Louis

and Mary Leakey at

Louis

and Mary Leakey at

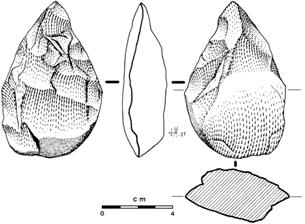

The drawing of an Oldowan handaxe was prepared by

José-Manuel Benito, and comes from Wikipedia.

It illustrates an important feature of Oldowan tools; namely that their

makers didn’t bother to make them symmetrical.

As we’ll see, later handaxes are usually superbly crafted to be

symmetrical to a high degree.

The Acheulean toolkit

About 1½ million years ago, a much more advanced

toolkit, the Acheulean suddenly appeared.

The technology was developed in

Why did they appear so suddenly? One theory is that their inventors Homo erectus, or the ‘mighty hunter’, mastered

the art of cooking at some point. This

reduced dramatically the amount of energy needed to digest his food – which

left more for powering his brain. Far

fetched? The scientists putting the

theory forward don’t think so.

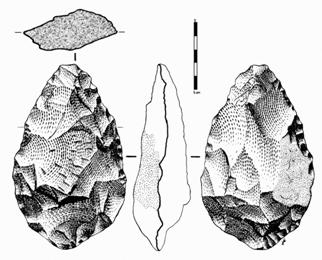

Whereas the Oldowan tools come in all sorts of shapes,

depending on exactly how the stone broke, the Acheulean tools were carefully

worked to produce the same shape each time.

This clearly involved a lot more work and a lot more skill. In particular it involved chipping the stone

from both sides to produce a neat symmetrical tool. Compare this drawing of an Acheulean handaxe,

also by José-Manuel Benito, with the Oldowan axe above.

Even

more striking, at least for whose who dismiss all our ancestors as stupid, is

this. Some smaller tools were made from

large flakes that were themselves struck from carefully-prepared stone

‘cores’. It must have taken an element

of real planning to produce the excellent products that have been found.

Even

more striking, at least for whose who dismiss all our ancestors as stupid, is

this. Some smaller tools were made from

large flakes that were themselves struck from carefully-prepared stone

‘cores’. It must have taken an element

of real planning to produce the excellent products that have been found.

How do we know so much about how these tools were

made? Because there’s a large band of

modern stone-knappers, whose joy-in-life is obtained by recreating them.

There’s evidence that Acheulean artefacts were much

more than just workaday tools. Many perfectly

good axes have been found, discarded unused (an experienced knapper can tell at

once whether an edge has been used or not).

Others have been found that are far too exquisite to be ordinary

workaday tools. Others still are ridiculously large. They were almost certainly used as gifts,

status symbols or even money (more).

The Acheulean toolkit was invented in

The Mousterian toolkit

The next development was the Mousterian toolkit, which

appeared around 200,000 years ago, and lasted until about

40,000

years ago. It’s associated

40,000

years ago. It’s associated  mainly

with the Neanderthals although, as we’ll see later, it’s not clear who actually

invented it. The name comes from Le

Moustier, a rock shelter in southern

mainly

with the Neanderthals although, as we’ll see later, it’s not clear who actually

invented it. The name comes from Le

Moustier, a rock shelter in southern

Mousterian technology was not a revolution, in the way

that the Acheulean system was. It was

more of an incremental advance.

For example, we’ve already discussed how Homo erectus prepared stone cores, so

that they could strike sharp flakes off them quickly and easily. These pictures of a Mousterian core come from

The World Museum of Man. With a bit of

imagination, you can see the scars where flakes have been chipped off. But the Mousterian toolmakers went

further. They mastered the art of

producing cylindrical cores. And from

these they were able to strike off longer flakes, with much longer cutting edges.

Another feature of the Mousterian toolkit is that it

contained a much wider range of tools.

For example, scrapers appear, specially adapted for dressing hides. I find it difficult to believe that folk

hadn’t been making things from animal hides for a long time. But no doubt these scrapers made their

preparation easier, and did a better job.

Spear heads appear too. We know

that folk were hunting with superb throwing spears some ½ million years earlier

– and very effectively too (more). But they will have had much less durable

points.

There’s something of a mystery about whether we, Homo sapiens, or the Neanderthals

invented the Mousterian toolkit. This may seem odd. But there was a time when we took it turns to

occupy an area of the

The Upper Palaeolithic

‘Upper’ means later, so we’re talking quite recent

now, from 40,000 years ago until around the end of the Ice age.

This is where things get complicated. The tools that people use become just part of

their culture. And I’m less confident

that I can make sense of it all. Part of

the problem of course is – almost – a surfeit of evidence. More and more sites are being

discovered. And of course they all tell

a slightly different story.

It’s clear however that the Neanderthals’ Mousterian

culture/technology evolved into the more sophisticated Châtelperronian culture. It is named after Châtelperron,

also in France. It lasted from 35 thousand

years ago, until around 29 thousand when the Neanderthals died out in most

areas.

Bone artefacts start to appear. The harpoon head in the picture is clearly

bone – as of course is the needle. The

general assumption seems to be that folk weren’t using bone until then. I find this difficult to believe. Until persuaded otherwise, I shall prefer the

thought that earlier bone artefacts have simply rotted away. You must decide for yourself what you think.

Around 40 thousand years ago, we Homo sapiens invaded Europe, bringing our Aurignacian

culture with us. Again it was developed

in Africa, some 90 thousand years ago I think.

But again it was named after a place in France, Aurignac in this case. It held sway until about 25 thousand years

ago. I’ve read that the Aurignacian

technology was developed independently in southwest Asia.

It’s striking how similar the two cultures were. It’s clear that there must have been a degree

of cross-fertilisation between us and the Neanderthals. We arrogant H. saps of course take it for granted that the Neanderthals were

copying us. And so they may have been

much of the time. But some scientists

have come up with evidence that the Neanderthals sometimes got there first (more).

After that, new cultures come thick and fast. And I’ve decided to give up. Wikipedia has a fairly comprehensive account,

though I suspect that even that is far from complete.

© C B Pease, February 08