A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home page

Boats and Sail

We will almost certainly never know

when humans first got on to the water.

reed

craft Colonising SE Asia Colonising America Colonising the Pacific Sail & Egyptian boats square rig fore-and-aft rig

I’m allowed to speculate in a way the scientists are

generally not. I reckon that it was

probably tens or even hundreds of thousands of years before we are ever likely

to have any hard evidence.

We discuss elsewhere

the notion that our ancestors of, say ½ million years a ago, were a good deal

smarter than they had previously been given credit for. We would never have believed them capable of

making superb throwing spears until some were found. It was one thing to find animal

shoulder-blades with spear holes in them.

To find the spears that made them was something else altogether.

But you never know.

Mud is a wonderful preservative.

One day we may find evidence of simple boats from that far back.

Reed craft

Closer to our time, we have a bit of a mystery.

Craft built from bundles of reeds have been found in  coast

of

coast

of

How is it that such similar vessels are to be found in

places so far apart? Did some mysterious

deity descend, provide seed for the reeds and pass on the technology? There are more prosaic explanations.

Here’s where I either go right out on a limb, or put

two and two together properly for the first time.

First we must remember that 150 million years ago,

Second, a group of scientists believes passionately

that we, or our immediate ancestors, went through a semi-aquatic phase; in

which we survived by spending much of our time in the water. We discuss it briefly here, but there’s more on the Internet under

‘Aquatic Ape Theory’. If there was such

a phase, then it could well have happened just as we moderns were splitting off

from other folk of the period. That

seems the best candidate to me anyway.

It looks to have been somewhere around 200 thousand years ago.

If so then we have fully modern humans, earning their

living swimming and diving in the water.

If ever there was an incentive to invent boats then this was it. And if the only material available was reeds,

then reeds it would have to be.

Eventually conditions improved and we were able to expand

out of our aquatic niche. We spread out

around the world, some of us keeping to the coasts and eventually reaching the

Americas, the Pacific islands and Australia.

Did we remember how to build reed boats throughout

long periods when we didn’t need them, or didn’t have any reeds? Well it seems that illiterate societies often

have specials castes of story tellers, whose role is to pass on ancient myths

and legends – accurately – and to tell them in an exciting and interesting

way. So I see no reason why not. A simpler explanation might be that, if you

want a boat and all you have is reeds, maybe there’s really only one way to do

the job.

Colonising South-East Asia

An article in Science (19.10.07) reckons that

South-East Asia  was

colonised using bamboo rafts, large enough to take up to 20 people. The idea is that a viable group would have to

comprise 5-10 women of reproductive age and a similar number of men.

was

colonised using bamboo rafts, large enough to take up to 20 people. The idea is that a viable group would have to

comprise 5-10 women of reproductive age and a similar number of men.

However a lively, even sharp, debate rages over how

far the colonisation was deliberate, and how far it was accidental. The following is my attempt to chart a

middle course.

The map comes from the Science article. It shows the coastline 22 ky ago. This is a bit later than the period we are

interested in. But it shows clearly how

much easier movement was when the sea level was much lower.

The first known colonising voyage was actually carried

out by Homo erectus folk, when they arrived on the  inventing

boats of some kind. The problem is that there’s no other evidence whatsoever of

their having any interest in boats. So

theory B is that a viable group somehow got swept across to

inventing

boats of some kind. The problem is that there’s no other evidence whatsoever of

their having any interest in boats. So

theory B is that a viable group somehow got swept across to

Modern humans were the first to leave any evidence of

having crossed the waters. The dates are

controversial, but a comprehensive article in New Scientist (27.10.07)

suggests 50 ky, for us to have got as far as Australia. How far was the sea

crossing accidental? Opinions differ.

Some scientists point out that the South-East Asian

waters were an excellent training ground for budding seafarers. There was no need for them to have any great

explorations in mind. Not only was the

sea warm, but both the coastal and deep waters provided superb fishing. So all they needed to do was to get better

and more adventurous in their fishing trips.

They could easily have ended up becoming quite serious seafarers. Remains have been found of deep-sea fish, such

as tuna and sharks, on numerous islands dating back to more than 40 ky.

There’s no direct archaeological evidence of sails in

these waters until after they appeared in the Near East a mere 7 ky ago. And yet a crude sail is such an obvious

innovation for anybody out in a boat. I

find it very difficult to believe that any resourceful people wouldn’t have

thought of it fairly soon after taking to the waters at all. Again we are reminded of the scientists’

common refrain that ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.’

On the other hand they didn’t actually need

sails. Sustained hard paddling by the

entire crew should enable even an unwieldy raft to make reasonable

progress. And of course you can paddle

against the wind.

With the water level so much lower, many of the

islands were well within sight of each other.

So if one got a bit overcrowded, then maybe it was natural for a viable

colonising group to take ship, or rather raft, and go and explore another

one. If much of this was done, then the

occasional group would almost certainly have been caught in a storm and get

swept out to sea. Either they would

perish, or they would get cast ashore on some distant land such as the north

coast of Australia.

Colonising America

The prevailing view is that America was colonised over

land. They were hunting big game, and

the game led them over  the

Bering Straights land bridge some 13½ years ago and down into America. But the journey sounds pretty horrific. And it will have required them to adapt to a

succession of different eco systems. Why

would they bother unless they were pretty desperate?

the

Bering Straights land bridge some 13½ years ago and down into America. But the journey sounds pretty horrific. And it will have required them to adapt to a

succession of different eco systems. Why

would they bother unless they were pretty desperate?

And now further evidence is beginning to shoot holes

in the theory anyway.

An article in New

Scientist (11 August 07) suggests a new theory, and one much more in

keeping with what we have been saying.

But first we should remind ourselves of a theory, also

aired in New Scientist, about first

primitive humans that left Africa. They

could easily have been fairly primitive Australopithecines

“just following the grass”. And there’s

evidence that it could have been some 3 million years ago. This goes against

traditional scientific thinking. But

animals do it. Why not primitive humans?

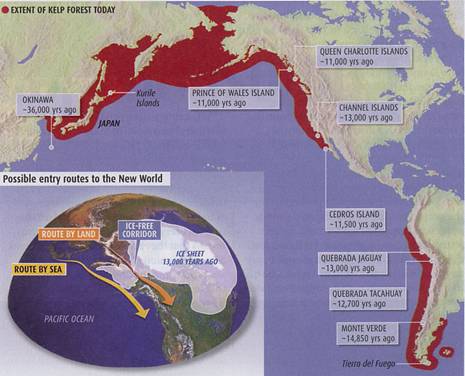

Now it’s suggested that modern humans followed the

coast around from Asia to America “just following the kelp”. This map comes from the N.S. article. The red zone shows where kelp was thought to have

been at the time. Which route would you choose?

Kelp is a wonderful habitat for all sorts of

nutritious marine life, so it’s an excellent food source for anybody with a

boat. There would have been no need to

conquer these hostile ecosystems.

Conditions would have been much the same all they way round. However, whenever the migrants found some

good habitat a bit further inland, then no doubt some would settle and put down

roots there.

Evidence is emerging of colonisation much earlier than

previously thought, around 20 thousand years ago I think. I’m a bit confused. The land bridge would have been even more horrendous

any earlier than 12-12 thousand years ago.

Did folk have boats long enough ago? There’s no direct evidence. The sea level was a good 100 metres (300

feet) lower than it is today – or possibly 50 metres (150 ft). Authorities seem to differ. We may eventually get some evidence

though. Underwater archaeologists are

beginning to contemplate diving to such depths.

But we can say that humans had been colonising remote islands as long as

36 thousand years ago. To reach Okinawa,

for example, would have needed a sea voyage of 75 kilometres. So the answer has to be yes.

What sort of boats?

Well it was probably too cold for reeds.

As we’ve seen, the South Seas were probably first colonised by bamboo

rafts. Once folk had got the idea for

boats, they would certainly have found something.

Colonising the Pacific

I’ve read many reports attempting to suss out when the

various more distant Pacific islands were colonised, by whom and from

where. To reach them would have needed

serious navigating skills, on top of the ability to handle boats. It’s not surprising that the colonisation

appears to have started only about 4 thousand years ago. I’ve not seen anything definite, so we’ll

concentrate on how these ‘primitive’ peoples might have achieved the

feats of navigation required.

When the Europeans began exploring the Pacific, they

were amazed to find our ‘primitive’ peoples inhabiting islands huge distances

from any mainland. Of course, said they,

they could not possibly have sailed there in their primitive canoes with no

instruments. So the Europeans invented

all sorts of fantastic scenarios, including the sinking of a great continent

leaving only the peaks above water. Total rubbish all of it. But even today there are pre-historians who

can’t bear the thought that these folk were actually as smart as we are.

However this changed in the late 1700s, when Captain

Cook studied the Tahitian canoes and navigation methods, and judged them to be

perfectly capable of long voyages. He

was told that if the sailors wanted to go East, they waited for the westerlies

to come. To come back, they waited for

easterly trade winds to return.

Many years ago, I read how the Polynesians navigated.

I can’t guarantee to have it exactly right.

But it went something like this.

First, we have to note that many Pacific islands

(presumably the taller ones) are most of the time adorned with a cloud

cap. And this cap can be seen even when

the island itself is way below the horizon.

Second, the Pacific skies are normally more or less

cloud-free, particularly (I’m guessing here) at night. This means that the seafarers were able to

get extremely familiar with the stars.

And they would sail towards ‘the rising’ of this star, or ‘the setting’

of that one. It must have taken

considerable skill and experience to judge this when the star was still high in

the sky. But clearly they were able to

do it.

I would guess also that the Pacific ocean currents are

generally a good deal weaker than they are in the North Atlantic, where the

Vikings did their momentous voyages. The

Atlantic currents regularly sweep you miles away from where you thought you

were. And if you can’t account for this

then you are in trouble. The Vikings

needed a gadget for estimating their latitude (their North/South-ness as it

were) to help keep them on course. I’ve not read that the Polynesians had such a gadget. But it was very simple,

and eminently inventable by any seafarer with the need. On the other hand, if you really know your

stars, then maybe you don’t need an instrument.

Sail and Egyptian boats

Now we come to Europe and the Mediterranean

waters. The earliest evidence of

seafaring on the Med. Dates to only 12-13 ky ago. Ánd even that is indirect. It comes from signs of human occupation on

Cyprus and the Greek island of Milos. Why

should this be? The science

article has an answer. The Mediterranean waters are almost barren of fish. There is little tidal movement, and the

temperature gradient of the water traps nutrients on the sea bad, far too deep

for sunlight to penetrate, and allow photosynthetic bugs to thrive. So why would they venture on to that

dangerous sea?

According

the the article, the oldest actual boats so far found are at most 10 ky

old. They are hollowed out logs like

this one, and have been found in the

According

the the article, the oldest actual boats so far found are at most 10 ky

old. They are hollowed out logs like

this one, and have been found in the

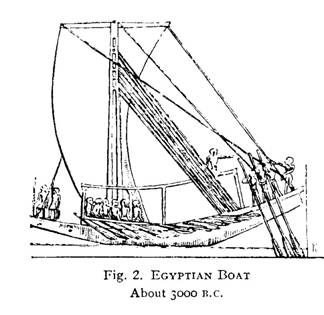

However civilisations first appeared around the  world

like a reed boat with a mast and sail.

We’ll probably never know what it was actually made from. This picture is of a slightly later boat,

around 5,000 years ago. Like the

following one, it comes from Romola & R.C. Anderson’s ‘The Sailing Ship’.

world

like a reed boat with a mast and sail.

We’ll probably never know what it was actually made from. This picture is of a slightly later boat,

around 5,000 years ago. Like the

following one, it comes from Romola & R.C. Anderson’s ‘The Sailing Ship’.

Like all early depictions, it shows the mast up in the

bow, out of the way. This is an

excellent arrangement in many ways. It

leaves plenty of room for cargo. And it

allows the ‘backstays’ to be taken to the stern at a good angle, to minimise

the stress on both rope and hull.

This was important.

The Egyptians didn’t have access to the big mature trees that we

northerners are used to. They had to

make their boats from smaller bits fastened together. Their hulls were inevitably much weaker and

floppier than they would have liked.

Indeed the next picture shows clearly a stout rope, running over

trestles from stem to stern. Other

pictures show this same rope twisted up bar taut.

There’s one small snag to having all the sail area up

in the bow. You can only sail down

wind. If the wind is in the north, then

lets say that you can sail anywhere between SSE and SSW. If you want to go anywhere else then you have

to get the oars out. And having all

those oarsmen on board is a heavy overhead.

Another feature of these early boats is that only the

middle part was actually in the water.

This is not clever from a sailing point of view. For both speed and stability, you need the

maximum ‘waterline length’ possible. On

the other hand it’s handy for loading and unloading from a beach. And the weakness of the hull may have given them

no choice.

Square rig

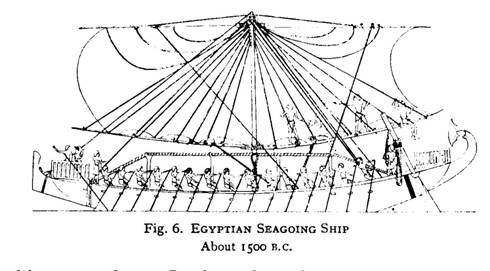

But by around 3½ thousand years ago, the mast had

moved to the middle. They won’t have

done this for fun. They must have

discovered that it gives  them

much more freedom over where they can go under sail.

them

much more freedom over where they can go under sail.

In doing so, the Egyptians invented what we would now

call Square rig. Think men o’ war like

HMS Victory or clipper ships like Cutty Sark (I’m British so I’m afraid I’ll

tend to give British examples.)

One is often asked why a sailing boat can’t sail into

the eye of the wind. In truth that’s the

wrong question. The correct question to

ask is “how is it possible to con the wind into pushing you against itself at

all?”

The answer is “with low cunning and

aerodynamics”. You have to fashion the

sail into a kind of poor man’s aircraft wing.

The closer to the wind you want to sail, the better your ‘wing’

approximation has to be. In particular,

the ‘leading edge’ of the sail has to be straight, and able to point straight

into the wind. This enables the sail to

coax the airflow gently round a curve, as in the coloured picture below. It is this finesse that provides the ‘lift’

on both an aircraft wing and a sail.

The square rig is a down-wind rig. A modern square-rigged boat is also quite

good ‘across the wind’. It can sail at

good speed, with the wind in the north, anywhere from east, through south to

west. The fact that the Egyptians kept

their large crew of oarsmen perhaps suggests that they remained somewhat

limited in this regard.

The ultimate development of the square rig comes with

the Men o’ War and the Clipper Ships. A

three-masted square rigger can cram on huge amounts of canvas. A clipper in particular can carry a full

cargo downwind at ridiculous speeds. But

upwind the rig is very poor indeed. The

clippers often preferred to go on round the world rather than face a return

voyage of headwinds.

One can think of many ways to stiffen and straighten

the leading edge of a square sail. But

they must all have proved impractical because none of them ever caught on.

The fore-and-aft rig

Instead,

the Egyptians invented the fore-and-aft rig.

This picture of a modern example

was taken by Colin Waters. It

shows a fore-and-aft rig doing what it does best – sailing close to the

wind. The burgee at the top of the mast

will have been fluttering more or less parallel with the leading edge of the

sail. Downwind, the fore-and-aft rig is

nowhere near as good as the square rig.

Instead,

the Egyptians invented the fore-and-aft rig.

This picture of a modern example

was taken by Colin Waters. It

shows a fore-and-aft rig doing what it does best – sailing close to the

wind. The burgee at the top of the mast

will have been fluttering more or less parallel with the leading edge of the

sail. Downwind, the fore-and-aft rig is

nowhere near as good as the square rig.

The earliest type of fore-and-aft rig to appear is the

lateen sail. It was probably invented by

the Nile sailors some 1500 years ago (around 500 AD). And of course it’s still to be seen there

today. We’ve all seen pictures of

it. It’s a natural progression from the

square sail, but it’s still not very good for upwind work.

The best upwind effect is obtained by attaching the

leading edge of your sail to a bar-taut near-vertical wire, as in a modern

yacht’s jib. The mainsail loses a

certain amount of thrust due to its being attached to the thicker mast. When the northern sailors caught on to the

benefits of the fore-and-aft rig, they gradually improved it to approach closer

and closer to this ideal.

The fore-and-aft is a go-anywhere rig. If well set up, it should be able to sail to

within about 45° of the wind. This means

that it can progress upwind in 90° zigzags.

So it can make reasonable progress in whatever direction the skipper

wishes.

Eventually, when steam reached the sea, sail declined

in importance. Today sailing is a purely

leisure activity.

© C B Pease, December 07