A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

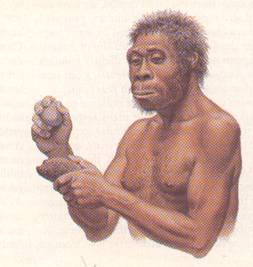

The arrival of the Mighty Hunter

Next came the Mighty Hunter, Homo erectus. During his

reign, the big cats and the last of the Australopithecenes

vanished. And H. erectus took over the whole of  His brain had grown to about half the size of

ours; around 750 cc.

His brain had grown to about half the size of

ours; around 750 cc.

H. erectus were

true people of the plains. We’ve talked

about our earlier ancestors being able to walk.

But there’s all the difference in the world between being ‘able to walk’

and being ‘a true walker – and runner’.

And H. erectus was the latter.

They had sacrificed their tree-climbing skills, by

acquiring long straight legs and arms.

No doubt there were many other adaptations as well. As a result they were no better climbers than

we are. H. erectus also acquired a small pelvis, a major cost as we’ll see

shortly.

As far as I can see, only one decent skeleton has been

found, of early H. erectus

anyway. It’s of a boy, ‘Turkana

Boy’. He was only 11 or 12 years old

when he died, but he was already nearly 5½ feet (1.6 metres) tall. The skeleton below comes from ‘Research Penn

State’.

But there was a more important sacrifice than mere

walking ability. Our  earlier

ancestors had retained the large pelvises of their ape forbears. This means that their babies were born in a

far more developed state than ours are.

But a large pelvis is incompatible with good walking. So it had to go. H.

erectus babies were born as helpless as ours are, with the brain continuing

to grow considerably after birth, just as ours do.

earlier

ancestors had retained the large pelvises of their ape forbears. This means that their babies were born in a

far more developed state than ours are.

But a large pelvis is incompatible with good walking. So it had to go. H.

erectus babies were born as helpless as ours are, with the brain continuing

to grow considerably after birth, just as ours do.

This has considerable implications for the way they

lived. It’s difficult to imagine H. erectus getting away with this burden

on their resources, unless they had a complex and stable social structure. So we have to imagine them living reasonably

settled lives in, say, village-sized communities.

There may be few complete skeletons. But a lot of skulls have clearly been found,

because the scientists have been able to chart a gradual increase in the size

of their brains, until its average was nearly twice the size of that of H.

habilis. This is the largest spurt

in brain size of any of our ancestors.

Even the one that led directly to us pales in comparison.

It needs some explanation. You can’t just grow your brain willy

nilly. Brains use a lot of energy, and

you have to have this extra energy available before you can develop your brain.

The classical explanation is meat.

The H. erectus

folk may well have started out mainly as scavengers, seeking out the remains

that animal predators had left – or driving the smaller ones off their

prey. If so, their new-found walking and

running abilities made them much better at it.

And it gave them a much richer diet.

As a result, they were able to shrink their guts, and

to reduce the amount of energy expended in digesting their food. So more energy was available for powering

their brains. They became better still

at acquiring meat … which led to a virtuous circle, and to this eventual

doubling of brain size.

I personally have no doubt that it also led to their

becoming serious hunters in their own right, whether or not they started out

that way.

H. erectus

inherited the ancient Oldowan toolkit from their Homo Habilis ancestors. But

at some point they invented a brand new one, the Acheulian toolkit (more).

Acheulian tools are more difficult to make than Oldowan tools, and they

need more strength. But they are much

more effective too. And the kit

contained a wider range of tools. Most

of them appear to be for butchering.

What is most striking about the Acheulian tools is

this. They are normally far better made

than they need to be to do the job.

‘Exquisite’ seems to be the appropriate word for many of them. Many of the tools were discarded completely

unused, presumably because they weren’t exquisite enough. According to Wikipedia, this suggests that

the roots of human art, economy and social organisation all arose as a result

of the development of these tools. I’d

prefer to see it put the other way round.

This craftsmanship ‘for its own sake’ arose as a consequence of all these things.

Even more importantly, these folk had the leisure to indulge in such

frivolities.

I’m slightly puzzled by the apparent absence of

weaponry in the toolkit. Perhaps their

weapon tips were made of bone or fire-hardened wood, neither of which would

preserve well. On the other hand, maybe

a well organised band of hunters doesn’t need high tech weapons to be

effective. In Canada there’s a place called

“Head-bashed-in Buffalo Jump”. It takes

little imagination to work out how the locals acquired their meat!

But where did H.

erectus come from? We have a bit of

a problem here. There don’t appear to

have been any climate changes in Africa to trigger a spurt in evolution just

then. Nor in Africa does H. erectus have any “clearly

identifiable immediate ancestors”.

There is a theory that extinctions are more to do with

the theories of Malthus. Malthus pointed

out that populations have the potential to expand exponentially, although in

practice they are self-limiting. He

believed that starvation, illness, war etc. were the likely causes of this

limitation. This theory leads naturally

to the conclusion that pressure from other hominids was the likely cause of

many of the extinctions. However it’s

not something that you can prove. And so

far I’ve only found one scientist who holds this view.

But a totally new explanation is gaining ground,

courtesy of Professor Richard Wrangham of Harvard. I first saw it in New Scientist (1.7.06), but now Science

(21.0.07) has corroborated it. It neatly

solves the problem of their being no explanation or evidence (without invoking

Malthus anyway) of how H. erectus

arose where he was supposed to.

In essence, he didn’t

In the past decade H.

erectus remains have been found in five non rift-valley sites, that were

very nearly as old if not  older

than the first evidence from the rift valley areas. It seems that H. erectus appeared almost simultaneously in Africa, East Asia and

somewhere in between.

older

than the first evidence from the rift valley areas. It seems that H. erectus appeared almost simultaneously in Africa, East Asia and

somewhere in between.

We discuss the Australopithecines in

Around the right time, 1.8 My ago, there was a pulse

of cooling. But it occurred in

Asia. It didn’t reach Africa. So it was Asia where the selective pressure

for rapid evolution was intense. Dmanisi

in Georgia seems to be the favoured candidate, because the finds have about the

right date (1.75 My). Both a skeleton

and simple Oldowan tools have been found there.

It’s also in the middle of the region over which H. erectus appeared so quickly.

The Science article that we

mentioned earlier describes some bones that have been found at Dmanisi. They’ve been dated to 1.77 My. They are clearly either of very primitive H. erectus, or of folk who are very

nearly there – but not quite. This

picture comes from the Science

article. Incidentally, I don’t think we

should be too worried if the dates don’t seem to tie up perfectly.

Then, as conditions deteriorated further, why would

not some of them have headed south where it was warmer – reaching

Cowen

reports evidence that these guys had fire at least a million years ago. He reckons that the degree of co-operation

needed to control, maintain and transport a fire is very high, which again

implies a proper social structure and organisation.

But

Cowen goes further. He can’t imagine a

camp fire without people wanting to chat.

Over time, the chat will have ranged wider and deeper, and the

‘language’ will have evolved to make it possible to discuss these things. So Cowen believes that the dawn of language

must have been about then. This is far

earlier than most scientists accept. The

received view is that language was ‘invented’ by us, Homo sapiens, some 15 thousand years ago. But of course it all depends on what you mean

by ‘language’. (More

on language.)

Fire and cooking

The Harvard university

primatologist Richard Wrangham also believes H. erectus were into fire – and also cooking. His theory is reported in both Science (15.6.07) and Sci. Am. (Jan.08). If it’s in these two august journals then we

have to take it seriously whatever Wrangham’s critics may say. Besides it fits in with the thesis that I

peddle throughout this site, namely that our ancestors were a good deal smarter

than we – or many scientists – give them credit for.

Wrangham’s argument is quite

different from Cowen’s. He doesn’t

believe that eating raw meat reduces the energy burden on the digestive system

enough to explain H. erectus’s

explosive increase in brain size. He has

established that cooking, both for meat and for vegetables, further reduces the

energy burden. After trying to eat

chimpanzee food, he says “I realised what a ridiculously large difference

cooking would make”. Cooking makes the job of the digestive system very much easier. So it releases more energy for other things like powering the brain.

We have to say that other

scientists reckon that H erectus

could have obtained the necessary extra energy simply by eating their prey’s

soft parts such as bone marrow and brain tissue. And it’s noticeable that carnivore animals go

straight for the soft unmentionable bits of their prey.

But I’ve not seen any

explanation of why our earlier ancestors couldn’t have eaten these soft bits

just as easily as H. erectus. Maybe H.

erectus were the first to have the idea, or maybe it needed the improved

Acheulian toolkit to gain access to them, but I shall continue to have

difficulties with both these explanations until I’ve seen them explained

properly.

Another problem for Wrangham

is that the evidence for fire taming anything like as early as this is very controversial.

If cooking had become an indispensable part of daily life, then many

scientists would have expected a veritable trail of stone hearths surrounding

scorched earth and so on. But such a

trail only appears within the past 250 thousand years at the earliest.

Before that, signs of

controlled fire are extremely few and far between. But they do exist. For example a site has been found in Kenya,

dated to 1.6 million years ago, in which a patch of scorched earth incorporates

a mixture of different wood types – and no signs of roots having been burned

underground. You don’t get this with

natural phenomena such as forest fires.

They both cover a wide area and scorch the roots. Lightning strikes are local like cooking

fires. But they involve only one type of

wood, and also scorch the roots.

In any case, how much does it

matter? After all, scientists regularly

tell each other that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”. How long would you expect the evidence of a

fireplace to last if it wasn’t in a protected cave or something?

Personally I’m very taken

with Wrangham’s idea. But you will have

to make up your own mind.

[Click for next chapter, the spear throwers.]

© C B Pease, February 08