A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

The first Hominids

The hominids are the folk who split off from a joint

ancestor with the chimpanzees called Ardipithecus

– and ended up with us. We know very

little about the early hominids. The evidence simply isn’t there.

There’s a good reason for this. Up to now we’ve been interested in the major

players on the world stage, the dinosaurs, or the entire gamut of mammals. And we’ve been interested in long time

periods. Patchy though the fossil record

may be (more), there are normally places that yield enough

fossils to give the palaeontologists a reasonable story.

But now we’re concerned with a tiny insignificant

group of primates, who lived in an area that was hopeless for preserving

stuff. There was probably very little

to preserve anyway, except a few skulls and perhaps a few more teeth. The rest will have been eaten by sabretooth

tigers.

However there’s enough evidence to say that our

evolution was pretty normal. Our early

ancestors diversified into other species.

Some persisted for quite a while, and some died out quite quickly. They’ve all gone now of course, except

us. Whether we simply out-competed them,

or whether we actively killed the competition off, we may never know.

Earlier ideas that some mystical force was guiding our

development have gone out of the window.

Our own line, the hominids (more) has up to

a dozen species in it. Or maybe only

half a dozen. The devil is in the

detail, and the palaeo-anthropologists have almost as many theories as they

have skulls to work on. This is why I

don’t intend to waste time going into it too deeply.

Our first serious

ancestors

I’ve got much of my information for this from Richard

Cowen’s ‘History of Life’. According to

him our first serious  hominid

ancestors were the Australopithecines

(nothing to do with

hominid

ancestors were the Australopithecines

(nothing to do with

Over that that time they developed quite a lot. But

Cowen describes them all as having “the brains of apes but the bodies of

men”. Their brain size was in fact very similar to that of the

smartest modern chimpanzees, at say 450

cc odd. They were smaller than us, at

around 65-110 lb. And they presumably

lived in social groups, like their cousins the chimpanzees.

Perhaps we should mention Australopithecines afarensis.

They are mainly famous for ‘Lucy’, a skeleton of a woman that was far

more complete than had been found before.

She was found in northern

More recently an even more complete skeleton has been

found (Scientific American, Dec. 06),

just 4 km away from where Lucy was found.

This skeleton was of a young girl, probably around 3 years old. She has been called Selam. However she lived a thousand year earlier

than Lucy.

Selam’s bottom half was fairly well adapted to

walking. Note the weasel words

though. We will be coming on to a

descendant that was much better adapted still to ground living. But her top half still retained a number of

adaptations suitable for life in the trees.

This has led to a typical scientific ‘debate’. Were Selam’s folk back among the trees? Were these climbing adaptations not yet

affecting their ground-based lifestyles too much, so that they were taking

their time to fade out? Or would Selam

lose them anyway as she got older. These

kinds of issues are meat and drink to those working in the field, but we can’t

afford to regard them as more than details.

There were two main lines of Australopithecines, the ‘robust’ and the ‘gracile’. Their bodies were similar. I’ve read that the ‘graciles’ evolved into

the ‘robusts’, but the report was around 1994 and it seems to conflict with

more recent material.

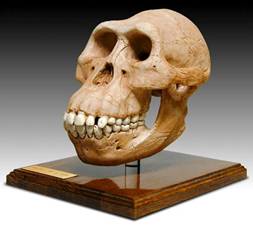

But the robusts had huge thick  skulls,

and would have looked seriously ugly to our eyes, not to say terrifying. They had small front teeth but huge

molars. This picture of the famous

‘black skull’ comes from Cowen. The

theory is that they found themselves in an environment where the only food

available was very coarse. So they had

to develop huge jaws, and massive muscles to work them with. The excrescence on the top was to provide an

anchor point for these huge jaw muscles.

The robusts died out around 1.4 million years ago. This incidentally is quite a long time after

the first Homos appeared (see below). Their lifestyle and food sources clearly

didn’t bring them into conflict.

skulls,

and would have looked seriously ugly to our eyes, not to say terrifying. They had small front teeth but huge

molars. This picture of the famous

‘black skull’ comes from Cowen. The

theory is that they found themselves in an environment where the only food

available was very coarse. So they had

to develop huge jaws, and massive muscles to work them with. The excrescence on the top was to provide an

anchor point for these huge jaw muscles.

The robusts died out around 1.4 million years ago. This incidentally is quite a long time after

the first Homos appeared (see below). Their lifestyle and food sources clearly

didn’t bring them into conflict.

As an aside, a report in Science (30.11.07) says that the robust males grew to around 17%

larger than the females, and took a lot longer to do it. This is reminiscent of modern gorillas. But it is a dangerous strategy, and only

makes sense if a large dominant male can collect together a harem of faster’

growing females and keep them to himself.

If this report is true, then it’s fairly rare behaviour among our

ancestors. Just how rare however is

still under study.

The graciles had a much better diet, either through

luck or because they were that little bit smarter. Their teeth and jaws were still pretty strong

– but nothing like those of the robusts.

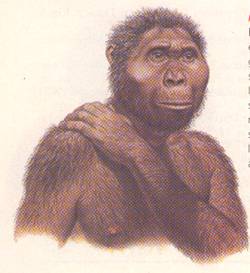

The lower picture is of a reconstruction, and comes from Bruce MacEvoy’s

‘Sculpture gallery’. The graciles were

taller and more lightly built.

Fossil evidence suggests that both types of Australopithecine were preyed upon by

the big cats of the time.

In 1999, Cowen was satisfied that we are descended

from the graciles. But I’ve since read

reports that suggest otherwise – in particular an article in New Scientist (1.7.06).

The standard theory is that the Australopithecines, with their short legs and lack of intellect,

were simply not equipped to wander far.

But the logic of this seems strange.

Animals don’t need intellect to follow their food source wherever it

leads. And the New Scientist article sees no reason why the Australopithecines couldn’t have done the same. It seems that an Australopithecine skeleton has recently been found in Chad, which

is 2500 miles away from their heartlands.

The article implies that it has been dated to 3-3½ million years ago.

This was a time when global cooling was encouraging

grasslands to spread from northern Africa to eastern Asia. This includes what

we now think of as the Sahara desert.

Dental studies suggest that, when it was in season, the robusts ate a

lot of grass. Either that, or they ate

small animals that ate grass. In fact

they probably ate both. How do we know?

It seems that teeth grow in layers like trees do. And different plants are differently fussy

about the rare carbon isotope carbon-13 that they take in. It depends on the precise details of the

‘photosynthesis pathway’ that each plant type uses. Some plant-types avoid carbon-13 like the

plague. Animals that live, even

indirectly, on such plants have very little carbon-13 in their teeth. Other types cope with it better. So a record of what you have been eating is

laid down in the layers of your teeth.

All the above being so, why wouldn’t the (robust) Australopithecines follow the grasslands

wherever they went? Just like the

animals did.

The matter is important because it has a bearing on

where Homo erectus, the mighty hunter, came from – as you can see by clicking ‘next

chapter’ below.

[Click for the development of stone tools.]

[Click for next

chapter, the first primitive humans]

© C B Pease, January 08