A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

Humans, how like

animals?

We are genetically very similar to modern chimpanzees

– very similar indeed. It seems that our

two DNAs differ by less than 1½%.

What

is the difference between us and animals? When did our line split off?

We need to stop and think about this for a

moment. The scientists have been

telling us for generations that animals are just machines. And many of us have believed them. And now we are told that they are almost

exactly the same as us.

It occurred like this.

In the 1920s, a group of ‘behaviourist’ scientists started to study

animals as if they were machines. You

did things to them and observed how they behaved. Now there’s nothing wrong with that (apart

from any cruelty aspect). At one time I

was involved in studying the human ear as a simple microphone. We knew that it was much more than that, but

we learned a lot by doing it

The mistake comes when you start actually to believe

it. And this is exactly what the

twenties’ scientists did. Indeed they

made “a hideous philosophical error”

(Colin Tudge, New Scientist,

11.3.95). The idea that animals are

just machines got transferred into dogma.

And from then on, no scientist was allowed to believe anything else.

There was no evidence for this. Anybody who lived or worked with animals knew

that the idea was nonsense, but nobody listened.

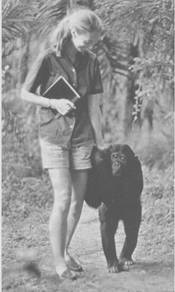

Around 1960, the young anthropologist Jane Goodall

went to study chimpanzees in their natural habitat. This picture  comes

from ‘a CBS/National Geographic special’.

Goodall found that actually they behaved very much like us. But she wasn’t allowed to say so. She couldn’t say that little Fifi was jealous

of his baby sister. She had to use words

like “Fifi exhibited behaviour towards his baby sister that, if exhibited by a

human child, would have been interpreted as jealousy”.

comes

from ‘a CBS/National Geographic special’.

Goodall found that actually they behaved very much like us. But she wasn’t allowed to say so. She couldn’t say that little Fifi was jealous

of his baby sister. She had to use words

like “Fifi exhibited behaviour towards his baby sister that, if exhibited by a

human child, would have been interpreted as jealousy”.

But Goodall’s pioneering work started the

breakthrough. There can be no doubt now

that animals experience all or most of the emotions that we do. Possibly less for the lower animals, but how

do we know?

Perhaps we shouldn’t lay all the blame on the

scientists. Before the coming of steam,

it suited us very well to regard our draught animals as little more than

machines. Even today it suits us to

regard our food animals in a similar light.

One of the capabilities that animals share with us,

I’m sure, is enjoyment. When we see

seagulls wheeling around in the updraughts against the cliffs, how can we doubt

that they are doing it for fun? There’s

no food for them up there. Of course

they are also honing their skills. But

that’s why we do things for fun – to hone our skills. Many of the skills that we acquire in this

way are pretty useless to us now. But

the principle must be the same.

So what is the difference between us and animals?

Well for what it’s worth this is my take on it.

I reckon that we are animals, with an extra layer of

computing power added.

Our basic brains are very much the same as that of

animals – at least the higher ones. That

is becoming clearer every day. And it’s

from this basic brain that we get the capabilities that animals have. For the higher animals at least, this

certainly includes a certain amount of thinking, culture, toolmaking and other

things that we used to regard as uniquely human.

But then we went on gradually to develop a major

upgrade. We acquired an extra layer of

more sophisticated brain, tacked on top.

This enables us to take these capabilities so much further than any

animal as to be out of sight.

That’s the best I can do.

When did our line split off?

It depends on who you ask. Let’s say between 5 and 7 million years ago,

possibly somewhere around

The common ancestor of both us and the chimpanzees

seems to have been a primate called Ardipithecus.

[Click for next

stage, Origins of Walking]

© C B Pease, Sept 07