A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

The rise of civilisation

The first glimmerings of civilisation are certainly

lost in the mists of time.

villages and towns cities

modern civilisations ‘Middle Asian’ civilisations civilisation good or bad? today’s civilisation

The dawn of

civilisation

There’s a strict definition of ‘civilisation’

somewhere, which rules out anything that isn’t pretty grandiose. However we can afford to be much less

fussy.

Indeed, it’s salutary to think that social insects

(ants, bees, termites and so on) have acquired many of the attributes of

civilisation. Closer to home, so have

many animals. Closer to home still, I’ve

read that first-time-mother chimpanzees have to be taught how to suckle their

first baby by their more experienced friends.

If this is true, then chimpanzee-kind would not last long without a

pretty closely-knit social group. Does that

imply the glimmerings of civilisation? I

like to think so.

Things change however some 1½ million years ago, with

the arrival of the mighty hunter (Homo erectus). By that time, the female pelvis had become as

small as that of a modern woman.

(Apparently a large pelvis is incompatible with serious walking

ability.) This meant that their babies

were born as helpless as ours are. And

their brains had to grow a good deal after birth, as ours do. So by H.

erectus time, if not before, we must have developed well-established and

permanent social groups, so that a young mother could be supported until her

children were self sufficient. Surely

that implies civilisation, if you don’t insist on defining it too rigorously.

Somewhere around that time, the first evidence of the

taming of fire appear. The evidence is

controversial. But I’ve found that new

developments usually get earlier as more is discovered. They seldom get

later. So for my part I’m minded to

believe that fire was first tamed at least as early as this. Indeed it could well have been a good deal

earlier. As we’ve discussed several

times, and as the scientists keep telling each other, ‘absence of evidence’ is

not the same as ‘evidence of absence’.

However in those days, a fire will not have been at

all easy to light. Once a camp had

acquired a fire, by whatever means, they had to keep it going at all

costs. This too would require a

reasonably large and cohesive social group.

By ½ million years or so ago, we see folk (Homo heidelbergensis to be precise)

making artefacts for show (the spear throwers)

– to impress the chief, their girlfriends, or whatever. They may already have had long distance

trade.

And of course by 20-30 thousand years ago (I wish I

could be more precise) we moderns (Homo

sapiens) had the leisure, the imagination and the motivation to produce

superb cave paintings (more). We certainly had long-distance trade,

personal adornment and so on. We were

burying our dead with ceremony and grave goods.

One could certainly say that we were civilised, even if our social

groups didn’t count as ‘civilisations’.

Villages and towns

When were the first villages? Of course it depends on what you mean by ‘village’. In a sense, a large cave would constitute a

village. But by and large, we British

don’t come from areas where there are caves.

My guess is that the H.erectus

folk will have made huts of some sort.

If so then they will certainly have clustered them together. Of course if they didn’t have huts, they will

have felt an even greater need to huddle together – into a village.

It’s even more difficult to imagine the Boxgrove folk

slumming it without pretty good accommodation. And southern

But huts don’t preserve well in the archaeological

record, and the first hard evidence that I’ve seen comes from around the end of

the ice age. Actually it’s amazing that

we can see even that far back. The

archaeologists normally  have

little to go except a pattern of post holes.

And even these take skill and patience to unravel. The post may have been left in position, to

gradually rot away, or it may have been taken out to be re-used. Either way, the hole’s ‘back fill’ is very

slightly different from the surrounding soil.

The archaeologists can learn how big the post was, how deeply it was

sunk into the ground, and even whether it was vertical or sloping.

have

little to go except a pattern of post holes.

And even these take skill and patience to unravel. The post may have been left in position, to

gradually rot away, or it may have been taken out to be re-used. Either way, the hole’s ‘back fill’ is very

slightly different from the surrounding soil.

The archaeologists can learn how big the post was, how deeply it was

sunk into the ground, and even whether it was vertical or sloping.

The experimental archaeologists use this information,

together with logic, common sense, knowledge of available materials and sound

engineering principles, to reconstruct what the hut might have been like. There are often only so-many ways of doing a proper

job. This picture is part of the Butser

Ancient Farm. It shows the Rolls-Royce

of ancient huts, the Iron-age roundhouse.

Notice the smoke drifting out through the thatch. The Butser people discovered that a hole in

the roof “to let the smoke out” was a good way to burn down your hut. Letting the smoke diffuse through the thatch

worked much better. And it made the roof

space a wonderful sterile and oxygen-deprived larder.

The picture that the archaeologists are unearthing is

more or less what you might expect.

Before and during the ice age, the only preserved evidence of occupation

is found in natural shelters like caves.

No doubt plenty of huts or even houses were being made in the less harsh

regions. But no evidence has so far been

found.

The earliest settlements that have been found date

from shortly before the end of the ice age.

They seem to have been used only at certain times of the year. Where people were the rest of the time tends

to remain a mystery. But gradually they

take on a more permanent  appearance.

appearance.

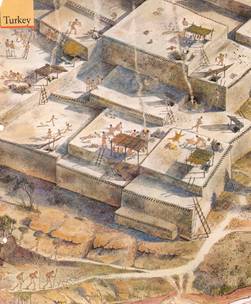

One of the oldest true towns so far found is

Çatalhöyük in Turkey, whose earliest remains date to 9 thousand years ago. It

seems to have been home to around 10,000 people. This was a stone age settlement, with

domesticated cereals and sheep. They

also hunted cattle, pigs and horses, and made use of many wild plants. However I’ve read that slag heaps have been

found there, indicating that they had already mastered the smelting of copper (more). The houses were full of paintings and

sculptures, many depicting extreme violence.

Çatalhöyük was

a weird place. Just houses and rubbish

dumps. As this picture from Scientific American shows, the houses

were so crammed in together that folk had enter them through the roof. Other sites of a similar age are now being

found, and they are all the same.

Çatalhöyük was not a city. We’ll see in a minute that

a city has to have all sorts of trappings that Çatalhöyük lacks. Their aren’t

even any cemeteries. Folk buried their

dead under the floor. There’s no

evidence of fortification either. So why

they crammed themselves in like this is a mystery.

Cities

Apparently a city has to have large secular buildings

(temples don’t count) with evidence of public administration and

accounting. There must also be evidence

of ‘zoning’ – administrative centres, residential areas, markets, industrial

areas and so on. And Çatalhöyük doesn’t

have any of these.

The earliest true city I’ve read of so far is Hamoukar

in northern Mesopotamia on the border with modern Turkey. Its earliest remains are some 6,000 years

old. Alternatively it may be its

neighbour Brak which could easily turn out to be  even

older. But both of these are in the

early stages of excavation.

even

older. But both of these are in the

early stages of excavation.

A much better known early city is Uruk (pictured) in

southern Mesopotamia. It used to be

thought to be the oldest ever city, and has been much more thoroughly excavated

These city states seem to have sprung up, lasted for a

thousand years or so, and then to have disappeared into the dust. No doubt there were different reasons for

this. Climate change was sometimes the

culprit. But there’s a more fundamental

one, which is an ever-present danger in dry areas – the poisoning of the

soil. River water always contains tiny

amounts of salt and other minerals, which it has dissolved out of the rock it

flows over. Ground water likewise. When you irrigate your fields with it, the

pure water evaporates, leaving the minerals behind in the soil. Over hundreds of years, the minerals build

up, and eventually the plants can’t cope.

Perhaps the end is violent, as seems to have happened in the Central

American civilisations. Here conditions

worsened, and the ruling classes demanded ever more dreadful sacrifices to

appease the gods. When the appeasing was

seen to have failed, the people turned on the elite and wrought terrible

revenge.

In wetter parts of the world, the land is watered by

almost pure water, straight from the clouds.

Not only that, but at certain times of the year, there’s often too much

of it. So any minerals get washed

straight through into the ground water beneath.

From there they find their way slowly to the nearest river or straight to

the sea. All this means that folk can

remain on the same land for a long time.

And they will normally obliterate evidence of earlier habitation.

Modern civilisations

When I was young, the Babylonians were billed as the

world’s first civilisation, having appeared nearly 4 thousand years ago. But every now and again, an exciting new

discovery would be made, of something even earlier. Then another one, earlier still. And so on.

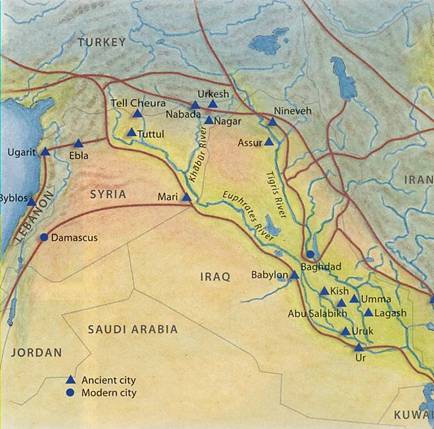

Most of the work seems to have been done in and around

the Fertile Crescent of Mesopotamia.

This is probably largely because of its Biblical significance. The map comes from Scientific American (Oct.

00). The brown lines are trade

routes.

But it’s also good archaeology country. It seems to have been dry for most of the

time since the ice age, with sand blowing about and covering over any

remains. This makes the sites difficult

to find, but it also preserves them for thousand of years.

The other advantage from the archaeologists’ point of

view is, as we’ve seen, that the people kept abandoning their settlements; and

that they often left behind a superb record of their way of life at the time.

The first civilisation uncovered so far is that of the

Sumerians. It seems to have emerged

about 6 thousand years ago, and to have lasted about a thousand years. It fits the official definition of a

civilisation, but it comprised a number of small city states which were

constantly at war with each other.

Although the dawn of music must extend way back, the first evidence we

have of any kind of music theory comes from the Sumerians (more).

If you want to know more about the Sumerians, it’s all

on the Internet.

Soon after came the ancient Egyptians, at around 5

thousand years ago. As we know, the

Egyptian civilisation was still going when the Romans came. The Nile valley is not subject to the

soil-poisoning problem, because the annual floods give the land a real

drenching. This both flushes the

offending minerals through and deposits a fresh layer of nutritious silt. So the Egyptians could carry on growing crops

on the same land for thousands of years with no trouble.

After that comes the Indus valley, at around 4½

thousand years.

Then come Akkadians, the Babylonians, the Hittites,

the Myceneans, the Greeks, the Assyrians, and many more that I’ve left out.

I’m slightly puzzled why so many of these

civilisations should be in relatively inhospitable places. You would think that the living would have

been much easier in areas where there was more reliable rain. Of course it could be the difficulties that

forced people to group together in ever larger communities.

‘Middle Asia’

It’s lucky that we keep saying “Don’t expect things to

be simple in this game”.

A report in Science (3.Aug.07) says that ‘a similar

awakening’ also happened over a wide swathe to the East of the area we’ve been

discussing – at much the same time.

The swathe extended from the Russian steppes to the

Arabian peninsular, where a series of ‘sprawling civilisations’ grew up. This was some 5 thousand years ago, so it was

after the Sumerians and about the same time as the early Egyptians.

We know very little about this so far, partly because

of the archaeologists “obsession with major river valleys”, partly on account

of the cold war and other goings on. But

the main reason seems to be that these civilisations didn’t last very

long. They suddenly collapsed just under

4 thousand years ago, possibly due to catastrophic climate change.

However, now that the archaeologists have got their

teeth into it, expect a lot more to be discovered.

Civilisation, good or bad?

We normally take it for granted that civilisations are

a good thing. Large communities attract

trade, and riches. These riches are

expressed in the form of art, some of which is superb. And so on.

But their huge achievements were inevitably based on

slavery. Until the coming of steam, everything had to be done by muscle power. And much of that muscle power was human. It’s difficult to escape the thought that,

for ordinary folk, the hunter-gatherer life or even the farming life, was much superior.

The excavations tend only to tell us how the elite

live. Sometimes we learn about the

middle classes, artisans, tradesmen and so on.

But we never learn anything about the huge army of servants, slaves and

others at the bottom of the heap.

I’ve also read, that these elites had a vested

interest in stifling technological innovation.

They saw change as a threat. It’s certainly remarkable that nobody can

tell us who invented the wheel, the windmill or the

watermill. It’s not too clear who

discovered how to smelt metals either. All of these brought huge benefits. But they were clearly invented by relatively

‘uncivilised’ people who kept no records.

I’ve got problems with the invention of writing too.

We’re told that the Sumerians did it.

But if so, they invented writing at the very moment that they emerged

from the shadows. It seems to me equally

likely that writing was invented by some unsung heroes; and that it was this

that made the rise of the Sumerians possible.

Maybe these civilisations were not the wonderful thing

for mankind that they are normally cracked up to be.

Today’s civilisation

Fortunately modern western civilisation seems to be

different. My theory is that it’s

because modern civilisation has been taken over by us ordinary folk. The priests and aristocrats are no longer

much of a force. And what gave the

middle classes their leg up? I would say

that it was the Industrial revolution

and the harnessing of steam!

But why did these huge advances happen when and where

they did, on the wild outer edges of a country itself on the edge of

civilisation? Why, for example didn’t

much of it happen in that much more central country, France? The historians may have an answer. But it could easily be precisely because France is so central.

Many argue that we developed the Industrial revolution

on the back of money made by slavery and colonialism. I’m not denying that we did these things and

a lot more besides. Neither am I denying

that unsavoury money helped.

But the basic argument is upside down.

I’m sticking my neck out in saying that, but to my

mind the facts are clear. Britain is

rich because we are an industrious and inventive people. And most of the time our country has been

reasonably well run. We also live in a

well-watered and fertile land, well endowed with mineral resources.

It was these homespun riches that enabled us gradually

to turn so much of the world red – and of course to make ourselves richer

still.

I’m the son of a Quaker. So I’m tempted to use the

Quakers as a prime example of the vital importance of the ‘industrious and inventive’ factor. It really is remarkable how many of the early

ironmasters and other industrial pioneers were Quakers.

The Quakers were pretty well detached from the rest of

Society. They had been persecuted, and

they felt that they needed money to protect themselves from further

persecution. Unfortunately part of their

code is scrupulous honesty. So if they

wanted to make their fortunes, they had to confine themselves to win-win

business opportunities. But

they were hard workers. And their

reputation for honesty made them well respected business men.

The Quakers also thought big. The railway pioneer

Edward Pease was predicting the entire country being criss-crossed with

railways – long before his Stockton and

Finding a win-win opportunity meant innovation, and

the railways are a prime example.

Everybody benefited from the railways.

Transport costs dropped through the floor, wherever a railway ran, and

this provided plenty of money for more railways. Business and Industry became

more efficient too. Fortunes were made

(and lost when the expansion went too fast).

True to the Quaker ethic, Pease was as keen for George Stephenson to

make a fortune out of his railway project, as he was on doing well out of it

himself.

Iron is perhaps an even better example. One of the first serious ironmasters was

another Quaker, Abraham Darby. He invented a new method of mass-producing

iron. This increased the supply, and

brought the cost down. Other innovators

found iron to be a better material than wood for all sorts of products. So demand increased. Darby and other ironmasters had to expand production, and to find better ways of making iron, and

of improving its quality still further.

Prices dropped massively and sparked off further increases in

demand. A wide range of new machinery

and other products were invented, which could not have been made until

plentiful cheap iron was available.

Again the entire Nation benefited.

I don’t doubt that unsavoury money

speeded these processes up. But they

would have happened anyway. Of that

there can be no doubt whatever.

© C B Pease, January 08