A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

The coming of

Steam

The harnessing of steam is one of

clock time and sun

time the railways

Before the coming of steam, ordinary folk like you and me would probably

have been tied to a life of backbreaking toil on the land, because that’s how

some 95% of us earned our bread.

I have to admit to an element of bias here, because my ancestors were

among the pioneers.

But to me the harnessing of steam was one of the Great Inventions of

Mankind, up there with writing and the wheel.

Before the coming of steam, everything had to be done by muscle

power. We tend to forget this when we

read Jane Austen and other pre-steam authors.

Their heroes and heroines were taken from the moneyed elite. And maybe their lives didn’t change very much

when steam came.

But most people’s lives were transformed. The Industrial revolution had already started

when steam hit it (more) but the

transport revolution hadn’t. (Canal

aficionados will be after my blood for leaving out their favourite transport

system. But I did admit to being

biased.)

Very soon after steam hit transport, it hit the farms too. Along came huge traction engines, powering

giant threshing machines, or hauling 10 furrow ploughs across the fields on

cables. And within a few years the

proportion of people working on the land was down to (I think) less than

10%. There were casualties to be sure. But prices tumbled and most people saw huge

benefits.

Clock time and Sun time

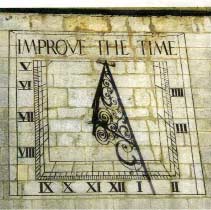

Before the coming of the railways, every village kept its own time. When the Sun was out, the church clock was  adjusted from a

sundial. These were often mounted on the

south-facing side of the church tower. This

one adorns the church at Market Harborough in Leicestershire. A wall-mounted sundial looks quite different

from the normal sundial that we are used to, but the principle is exactly

adjusted from a

sundial. These were often mounted on the

south-facing side of the church tower. This

one adorns the church at Market Harborough in Leicestershire. A wall-mounted sundial looks quite different

from the normal sundial that we are used to, but the principle is exactly  the same. The gnomon (pointer) still points to the Pole

Star, but it points backwards through the fabric of the building.

the same. The gnomon (pointer) still points to the Pole

Star, but it points backwards through the fabric of the building.

Time ‘of the clock’ was regarded as inferior to true Sun time – and for

good reason. If you look up ‘The

Equation of Time’ on the Internet, you will find that ‘clock’ time and ‘Sun’

time can differ by up to ¼ hour at certain times of the year. It has to do with the vagaries of the Earth’s

orbit. This is why, in our northern

climes, the mid-winter mornings carry on getting darker for several weeks after

the evenings have begun to lighten. You

hadn’t noticed this? It’s true. And it happens because ‘clock’ time is

averaged out over the year. If you reset

your clock regularly from a sundial then this wouldn’t happen.

Of course the railways couldn’t be doing with all these different

times. Over the 1840s they gradually

adopted Railway Time (Greenwich Time) for all their services throughout the

country. Clocks were extremely accurate

by then, as this picture of the 1837 master clock from Euston Station in

Unfortunately most of

The railways

Before the coming of steam, travel was slow, expensive and

dangerous. This picture comes from the

Northern Echo  Railway Centenary

Supplement, and it shows “a heavily laden stage wagon plodding slowly along

under eight horse power”. Leisure travel was the exclusive privilege of the

rich:

Railway Centenary

Supplement, and it shows “a heavily laden stage wagon plodding slowly along

under eight horse power”. Leisure travel was the exclusive privilege of the

rich:

John Gilpin’s

spouse said to her dear –

Though wedded we have been

These twice ten tedious years,

yet we

No holiday have seen.

William Cowper (1731-1800)

Gilpin was real, and a wealthy man. Yet Mrs. Gilpin’s

idea of a 20th anniversary ‘holiday’ was a day out, by chaise and

pair, to a famous local eating house! (I

can recommend the tale of “John Gilpin”. It’s on the

Internet. His adventures, trying to follow his family to the pub on horseback,

are amazing.)

However then came the world’s first successful steam ‘demonstrator’, the

Stockton and Darlington Railway. And  within a very few

years, the railway companies were taking us ordinary folk to the seaside in

trainloads – for very little money. And

we ordinary folk had the leisure to go.

within a very few

years, the railway companies were taking us ordinary folk to the seaside in

trainloads – for very little money. And

we ordinary folk had the leisure to go.

The next few pictures come from the Stockton &

Darlington website. The first

depicts the ceremonial opening of the Railway in 1825, and shows some of the 38

wagons being hauled by George Stephenson’s ‘Locomotion’. The wagons at the front weren’t meant to  have people

in. They were already filled with coal

and flour. A coach, called ‘Experiment’,

was provided for passengers. It was

thought that only rich people would want to travel on the Railway. How wrong can you be? The second picture shows a modern replica of

the locomotive.

have people

in. They were already filled with coal

and flour. A coach, called ‘Experiment’,

was provided for passengers. It was

thought that only rich people would want to travel on the Railway. How wrong can you be? The second picture shows a modern replica of

the locomotive.

Here is an unashamedly Pease-centred account of how it all happened.

Edward Pease was a Quaker businessman, born in  North-East of

North-East of

The Quakers thought big. And they

had a special pact with God that allowed them to make as much money as they

liked, as long as it was a by-product of doing good. All this slow and painful travelling gave

Pease plenty of time to ponder the thought that “there’s got to be a better way

than this”.

So by 1817, at around 50, Pease had retired from the woollen business to

concentrated on putting the ideas he had had into practice.

The invention of crude wooden rail-ways, plate-ways, or wagon-ways are

lost in the mists of time. But by the

late 1700s, reasonably good ones were being used in mines, both underground and

around the pithead. And Pease knew that

a horse could draw 10 tons along a level rail-way, whereas on an ordinary road

it could draw “scarce a ton”. He also

knew that mine owners were beginning to build private railways to carry coal

from their mines to nearby large towns.

So he developed the concept of the railway as the new King’s Highway.

That is to say, a public rail road on which

hauliers would pay to transport their

wagons. It didn’t work out quite like

that, but the principle was sound.

There had long been a plan to build a colliery railway from the

“… if the railway be

established, and succeeds, as it is to

convey not only goods but passengers (my italics), we shall have the whole

of

So, unlike all previous railways, the Stockton and Darlington was to be

a Public railway, open to both freight and passengers on payment of a fee.

As soon as word got round that Pease was serious, George Stephenson

walked into his life. The well-educated  Quaker businessman,

and the self-taught engine-wright from the coalfields,

hit it off at once. And the two remained

friends for the rest of their lives.

Stephenson was given the job of surveying the line. He introduced Pease to his latest colliery

steam-engine, Blutcher – worth, as he put it, 50

horses. Pease was converted, and his

railway became at least partly a steam railway.

Quaker businessman,

and the self-taught engine-wright from the coalfields,

hit it off at once. And the two remained

friends for the rest of their lives.

Stephenson was given the job of surveying the line. He introduced Pease to his latest colliery

steam-engine, Blutcher – worth, as he put it, 50

horses. Pease was converted, and his

railway became at least partly a steam railway.

One of the plans had been to dig a canal for the level parts of the

route, and resort to a railway for the hillier parts. But Pease was having no transhipments en

route. On another occasion, Stephenson

pointed out that the direct line to the coalfields didn’t go near Darlington. He was put straight very firmly. “George, thou must think of Darlington : thou must remember it was Darlington sent for

thee.”

George Stephenson did not invent the steam locomotive. The first serious (stationary) steam engine

was built by one Thomas Newcomen nearly a hundred

years before (around 1710 during Queen Anne’s time). It was huge, very inefficient and was used

for pumping out tin mines in Cornwall.

Early steam engines worked by vacuum.

We won’t go into it, it’s on the Internet. But the main points are that it didn’t matter

too much how big they were, or how inefficient – and there was no need for a

dangerous pressurised boiler.

But a locomotive had to be small, light, powerful and economical – and

reliable too. Again others had shown

the way, but none of their efforts came to much. Stephenson’s great achievement was to make it

all happen.

For a locomotive, you have no choice but to resort to high pressure

steam, and find a way of making it safe.

You also need a small but very powerful furnace. The ‘steam draught’ was invented, I think by

Stephenson. It’s what makes steam

engines chuff, and it makes the fire burn with terrible ferocity.

Meanwhile, the businessmen of Liverpool and Manchester were being held

to ransom by their local canal company.

They saw what was in progress across the Pennines, and they wanted one

too. But they had far more money to

invest, and they wanted a railway bigger, better, faster and more

reliable. Stephenson was hired and,

with all this money and the experience of the S&D, he gave them all

three. With his new locomotives,

including his famous ‘Rocket’, he was able to make the Liverpool and Manchester

another great step up. But it was still

the S&D that showed the way.

The railways were a major part of the Industrial revolution, and it’s

difficult sometimes to separate out the benefits that these two massive

developments brought to mankind. But

cutting transport costs was of itself a huge advance.

Within a very few years railways were criss-crossing the country, just

as Edward Pease had predicted.

Stephenson’s son Robert was a major driving force. British contractors were criss-crossing much

of northern Europe with railways too.

The French railways run on the left to this day (if you’ve travelled on Eurostar, you will of course have spotted this as soon as

you emerged in France). If my memory

serves, the Portuguese and Italian railways also run on the left.

These days, large

power stations are the only economic application for steam. But you can still experience steam-driven

fairground rides. And you can watch

steam traction engines drive traditional farm machinery. I’ve not heard tell of the huge ploughing

engines being demonstrated. Maybe the

risk of cable breakage is considered too high for these safety-conscious times.

These days, large

power stations are the only economic application for steam. But you can still experience steam-driven

fairground rides. And you can watch

steam traction engines drive traditional farm machinery. I’ve not heard tell of the huge ploughing

engines being demonstrated. Maybe the

risk of cable breakage is considered too high for these safety-conscious times.

In many places round the world you can ride behind a steam engine on a

‘heritage’ railway.

This picture of ‘Bittern’ was taken by Dave Warwick. Bittern is an identical twin of the world

steam speed record holder ‘Mallard’. She

has been lovingly restored from the ground up by the Watercress Line. I played a small part in the restoration,

which is why I’m devoting space to it.

The Watercress Line is based at New Alresford

(‘new’ because it’s only about 800 years old).

I’m told that Bittern has been restored to a much higher standard than

Mallard herself. So she should be able

to go quite a bit faster if the opportunity arose. But, as the picture shows, she has been

restored to be used; not to be incarcerated in a museum like poor Mallard.

Cars and lorries took transport up to the next level, and the aeroplane

took it to the next level still. But to

my mind, neither revolutionised ordinary people’s lives the way steam and the

railways did.

© C B Pease, April 08