A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET

click

for Home Page

The strange

Triassic animals

During the Triassic, dinosaurs and primitive mammals

were beginning to appear. Flying reptiles ruled the skies.

early mammals

The Triassic lasted from 245 to 200 million years

ago. It began with the ‘the Great

Dying’, the worst mass extinction since the Cambrian explosion (more).

And it ended with another lesser extinction. The great supercontinent of Pangaea was beginning to break up. And, whatever the space aficionados may say,

plate tectonic upheavals seem to have been the cause of both extinctions.

When conditions recovered, much of the planet was

empty and waiting for the few species that survived to expand into it. They did, and they developed in all sorts of

strange ways. It took them a while. All the creatures I’ve been able to find seem

to come from the late Triassic.

Pangaea extended from pole to pole. And whereas the climate over most of it was

hot and dry, the

Very few fossils have come down to us from the

Triassic Period. For a long time, the

only thing that palaeontologists had to go on was a few teeth and the

occasional identifiable bone. The teeth

in particular looked very much like dinosaur teeth. So in strict accordance with ‘Occam’s Razor’

(“always take the simplest explanation that fits the facts”), the creatures

were identified as primitive dinosaurs.

And the story was put about that the Triassic was the age of the early

dinosaurs.

Then complete skeletons started to emerge. And they weren’t dinosaurs at all. To be sure there were a few genuine early

dinosaurs among them. But this was the

age of a wide range of weird and wonderful animals, most of which died out in

the extinction that brought the Triassic to a close.

Wikipedia gives a comprehensive account, quoting all

sorts of strange names. We’ll confine

ourselves to a couple of main storylines.

The ‘crocodilians’ (crocodiles to you and me) were one

of the species that survived the second extinction. From what we’ve said about the climate, we

must imagine them mainly occupying the

Apparently so.

But palaeontologists had to study complete skeletons in great detail to

reveal their crocodilian nature. You or

I would never have guessed it in a million years. And as long as they had only a few teeth and

the odd bone to go on, neither could the palaeontologists!

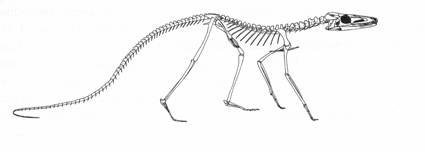

Actually, if you look carefully at the skeleton, you

will see that the way its legs are attached is a bit weird. We discuss elsewhere

how amphibians had to stop ‘waddling’ before they could be regarded as true

land animals. The creature that provided

this skeleton may have been basically a crocodile. But it was clearly on its way towards being

able to walk properly.

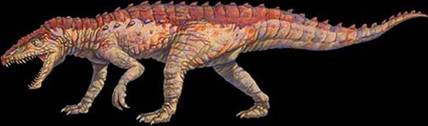

And it all makes sense. These creatures were the forerunners of both

the dinosaurs and the mammals. The

aggressive-looking creature above (copyright Joe Tucciarone) may look like a

dinosaur. But in fact he’s Postosuchus

or ‘post crocodile’. He lived in the

late Triassic, some 220 million years ago, and weighed nearly a ton.

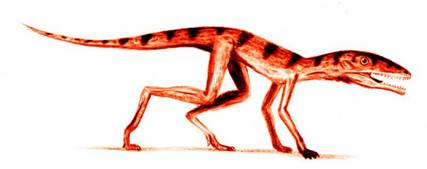

According to Wikipedia, these crocodilians were the

forerunners of the pterosaurs, or flying

reptiles, as well. The creature on the

right is an ornithoderan. These

apparently evolved into the pterosaurs “and a variety of dinosaurs”. Does this imply that other dinosaurs had

different roots? I can’t tell you.

But

all this was news to me. Other sources

have suggested that the flying reptiles appear in the fossil record quite

suddenly and already fully developed.

Hopefully the answer is that these other sources are out of date.

But

all this was news to me. Other sources

have suggested that the flying reptiles appear in the fossil record quite

suddenly and already fully developed.

Hopefully the answer is that these other sources are out of date.

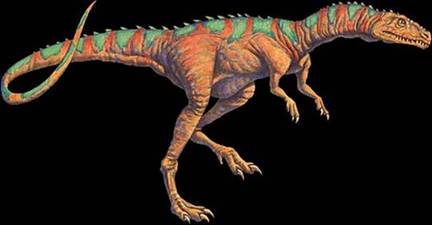

As we’ve mentioned, there were early dinosaurs around

too. This one (also copyright Joe

Tucciarone) is Chindesaurus. He’s a

primitive theropod, and also lived in the late Triassic. The theropods are widely acknowledged to have

been the ancestors of birds. And by adorning his specimen with bright

colours, Joe is suggesting (I think) that the theropods may have been sporting

feathers even as early as this.

Certainly signs of feathers have been found on theropod fossils from

long before flying was even on the horizon.

They may have been found on other dinosaurs too. I’m not too clear about this. Feathers are an excellent way of keeping cool

when it’s hot, and warm when it’s not.

And if you want to adorn yourself with bright colours, then feathers are

the way to go.

Early mammals

Primitive

mammals appeared at about the same time, though I’m not sure where they came

from.

Primitive

mammals appeared at about the same time, though I’m not sure where they came

from.

But here’s an interesting thing. The dinosaurs and the birds kept the

reptiles’ not-very-good lungs. And at

some point they added to supercharger to it (more)

which is why modern birds have far and away the best breathing system on the

planet. We mammals evolved our own lung

system, which is much better than reptilian lungs. But it’s not a patch on those of birds.

The early mammals were about 10 cm long and ate

insects. They quickly evolved the

ability to provide milk for their young.

This enabled them to look after their babies much more effectively, and

enabled them to be born less developed.

The early mammals are also thought to have been mostly

nocturnal, which kept them out of the way of the reptiles and dinosaurs.

This is the only authoritative picture I’ve found so

far of a Triassic mammal. It’s a bronze

sculpture of Megazostrodon, from the

According to Wikipedia, Megazostrodon is widely

accepted as being one of the first mammals, appearing in the fossil record

around 200 My. It had a few

non-mammalian characteristics, and is likely to represent the final stage of

the transition between ‘cynodont’ or mammal-like reptiles and true mammals.

Megazostrodon was a small furry shrew-like animal,

between 10 and 12 cm long, and it lived from the late Triassic to the early

Jurassic. It had a much larger brain than its cynodont relatives. And the enlarged areas were those that

process sounds and smells. This

reinforces the theory that it was nocturnal.

Wikipedia also offers us this picture of

Tricodonta. Note the ‘a’ on the end of

the name. Tricodonta is not a single

animal. It represents a group of early

mammals. Unlike Megazostrodon, the

Tricodonta had all the features of true mammals. Their line lasted from the late Triassic to

the late Cretaceous.

The name means ‘three conical teeth’, which is a

feature that they all shared. They

probably lived on small reptiles and insects.

However some of them appear to have been able to take on small

dinosaurs.

Triassic Plants

Several important plants survived both extinctions,

yielding descendents that are still around today. Wikipedia gives us the cycads, the ancestor

of the Ginkgo biloba and ‘the’ Spermatophytes or seed plants. In the northern hemisphere, conifers also

flourished, whereas the seed ferns preferred the south.

Triassic marine

life

Wikipedia implies that modern coral first appeared in

the Triassic, though that may not be what they actually mean.

Very few fish lines survived the Permian extinction,

so the fish fauna was very uniform and boring.

That’s not to say that they weren’t plenty of them  though. And there were many types of marine reptiles

to feed on them.

though. And there were many types of marine reptiles

to feed on them.

Perhaps the most famous of the Triassic marine reptiles

are the ichthyosaurs. This picture, from

UCMP Berkeley, is of an early ichthyosaur, from the Triassic. Later they developed into superb swimming

machines, looking for all the world like dolphins. But dolphins are mammals, and the

ichthyosaurs were reptiles.

This similarity represents a superb example of

‘convergent evolution’. There’s possibly

only one way to design a really-good fast-swimming predatory sea creature. And the marine reptiles, and

later the marine mammals, gradually homed in on it.

© C B Pease, February 08