A TIMELINE FOR

THE PLANET click for Home Page

Animals invade

the land

The animal kingdom didn’t invade the land until around

50 million years after the plant kingdom.

This gave the plants plenty of time to become well established; and to

provide an unwitting food supply for the marauding animals.

creepy-crawlies insects large animals (i.e. fish)

Even then it was only creepy-crawlies – arthropods to

be precise. These were the ancestors of

insects, spiders, crustaceans (crabs etc.) and many other small creatures. Large animals came some 70 million years

later still.

Now for a sea creature to develop the capability to

survive on land may seem like a very tall order. But in fact it can be done in easy

stages. And the right place to do it is

something like a tidal river estuary – with plenty of mud. Rotting land plants will have generated

plenty of nutrients for the rain to wash down into the water. So estuaries will have been teeming with

life, just as they are today. But they

will also have been dangerous places, with far fewer hiding places than many

other regions.

One potential ‘place of safety’ is very shallow

water. Shallow water tends to be

severely short of oxygen. We’re talking

mudflats here, mudflats in the baking sun.

The cool swiftly flowing streams that salmon use for spawning don’t

suffer from this problem. A creature

that can get at least a little oxygen direct from the air can escape to this

place of safety, where its predators can’t follow it. I don’t know about arthropods and insects,

but many fish today have primitive breathing equipment to enable them to do

this.

There’s also the little matter of the tide. In many places the tidal range will have

been many metres, just as it is today.

So animals of all sizes will often have found themselves stranded in

little shallow oxygen-depleted pools, with the need to survive until the tide

came up again.

The ability to spend some time out

of the water brings additional benefits.

There will have been quite a lot of food in the shallow water and out on

the open mud; courtesy of the plants and bacteria.

Once a creature can spend a little time out of the

water, the pressure will be on to be able to spend more time, and to be able to

move further and further in search for food.

This probably wasn’t a problem for the creepy-crawlies. But the larger fish had a lot of evolving to

do before they could master the land.

Fortunately the fossil record has come up trumps here, as we will see in

due course.

Creepy-crawlies invade the land

The first animals of any kind to invade the land were

arthropods, things like spiders, centipedes and mites. By chance, the arthropods were already

reasonably well suited to a future life on land. They had an almost waterproof shell,

presumably for protection. They were

strong for their size, and walked about the bottom on good sturdy legs. Unfortunately these early pioneers are

known only from fossilised footprints.

So we don’t know too much about what they were like.

It is known however that some of them dined off

organic debris. This was available

underwater as well as in the bogs and tidal margins. And of course there was also a supply ready

and waiting among the low-growing plants that had invaded the land 50 million

years earlier. So it’s easy to see how

they could have been tempted, bit by bit, into ever more hostile territory –

adapting as they went.

Their main challenge was to master the art of

breathing air. As we’ve seen, this too

could be a gradual process. Water in

boggy places can be very rich in food but, like the tidal margins, seriously

lacking in oxygen. Hence the

evolutionary pressure to get oxygen from both air and water. After that came the challenge of protecting

oneself against drying out. But again,

this could be a gradual process. The

better protected a creature was, the further up the beach it could roam in

search of food. The basics were already

there as we’ve seen.

Once the mites and other small plant-and-debris-eating

beasties had established themselves on land, larger carnivorous arthropods

could follow them. And they did. Pieces of a scorpion around 9 cm long have

been found from these early Devonian times.

Insects invade the land

I’m not at all clear when insects first invaded the

land, or even what they were like. I did

read that signs of insects on land don’t

appear until the late Devonian, some 70 million years after the arthropods made

the jump. But more recently I’ve seen

reports that they were around soon after the arthropods, around 400 million

years ago. And what is more, they seem

already to have been flyers (more).

Large animals invade the land

We know far more about how the fish invaded the

land. The fossil record has come up with

no less than six  different

species, each being slightly more land-adapted than the last. The entire process was completed within a few

million years

different

species, each being slightly more land-adapted than the last. The entire process was completed within a few

million years

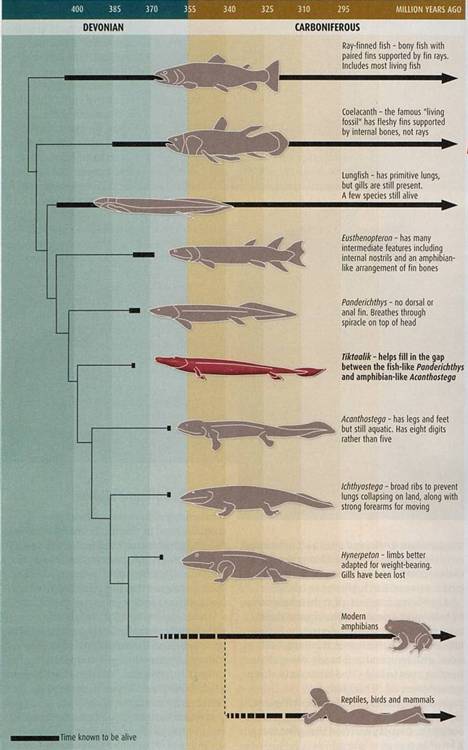

This superb diagram comes from New Scientist (9.9.06). The

top three fish types provide background information. If you know your fish, then skip this

paragraph. As far as I know, they are

the only three fish types still around today.

The first is the ray-finned fish.

The vast majority of fish today are ray-finned. Their fins are relatively flimsy affairs,

only really suited to guidance duty.

Next comes the lobe-finned fish.

Their fins have bones in them, and are strong enough to enable their

owners to flop about on the mudflats, as we discussed earlier. (Just to be perverse, the authors chose the

coelacanth for the diagram. The

coelacanth lives in deep water.) The

third fish, despite its name ‘lungfish’, doesn’t actually seem to be part of

our story. Its niche today is freshwater

lakes and rivers that dry up periodically.

The lungfish dig holes in the bottom and hibernate until the water

returns. The holes they make are

characteristic, and similar holes have been found from the earliest lungfish

times (early Devonian).

The next six animals range progressively from fish

with slight adaptations to life in the tidal margins, to a true amphibian. The red one in the middle is Tiktaalik. With a name like that, it was clearly found

in Inuit territory, north east Canada to be precise. It’s the most recent find, and the most

exciting, because it fills a gap that was worryingly large. Tiktaalik was almost exactly midway between

fish and land animal.

I’ve not been able to learn much on the breathing

front. Lungs are soft tissue and don’t

preserve well. However Tiktaalik certainly had gills, and

palaeontologists seem to think that it had lungs as well. I think some of the less-adapted animals are

thought to have had an air-breathing capability of sorts also.

It has to be said that these six creatures don’t seem

to have evolved from one another, because they lived at much the same

time. But they could all have evolved

separately from lobe-finned fishes. Each

then found a niche that suited it for a while – until better adapted animals

out-competed them.

Amphibians’ legs stick out at the side, and can only

support the animal’s weight by dint of sheer muscle power. So they have to walk by ‘waddling’. This is not a good engineering design,

because even standing still is hard work.

Small creatures have no problem with it why?. And it’s O.K. even for large ones, if they

spend most of their time in the water.

But we can’t say that animals had truly mastered the

land until they stopped  this

waddling – until their legs moved to under

the body, as in dinosaurs and mammals.

This enables skeleton to support the animal’s weight directly. No muscle power is needed just to keep us

up.

this

waddling – until their legs moved to under

the body, as in dinosaurs and mammals.

This enables skeleton to support the animal’s weight directly. No muscle power is needed just to keep us

up.

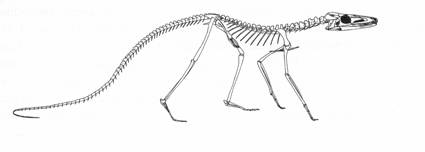

This skeleton is from Richard Cowen’s ‘History of

Life’. Cowen calls it a ‘crocodile’ from

the late Triassic (around 200 million years ago). To be so described, it must have a lot of

crocodilian features. But the way its

legs are attached is not one of them.

It’s just weird. The skeleton

may well be able to support the animal’s weight without help from its

muscles. But the whole arrangement is

still pretty flimsy. However it makes a

good deal of sense, as a possible immediate common ancestor of dinosaurs and

mammals.

This means that land animals were able to thrive for

more than 100 million years, despite the handicap of being waddlers.

© C B Pease, February 08