A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET

click

for Home

page

Continental

Drift

These maps show a succession of two or even three

different supercontinents, stretching back over a thousand million years. Not surprisingly the evidence gets

increasingly uncertain as we go back in time.

However scientists believe that there were several more even earlier supercontinents – at more or less 500 million

year intervals – stretching back until the planet was young.

We’ve all heard of Continental Drift by now, with the

different land masses wandering all over the globe. To begin with it was just theory. But now satellites can actually measure the

movement. On average it’s about 15

millimetres a year, or about the speed that your fingernails grow. Some are moving much faster. The Indian landmass, for example, is

galloping northwards at around 2 centimetres a year; and a huge chunk of it has

already buried itself beneath the underbelly of

Geologists and Palaeo-geographers have worked out how

the landmasses have moved in the past – how they have clumped together to form

super-continents, and then split up again and gone their separate ways.

The maps

These maps don’t show the actual shape of the

continents in times past. Neither could

they. A lot of land has certainly been

eroded away since, and more will have been deeply buried under other land – as

These images simply show the believed disposition of

present land masses at the time.

There are thought to have been at least 3

supercontinents, even earlier than the ones we depict below, stretching back

more than 2½ thousand million years.

This was the heyday of bacteria, when they were the only life

around.

The hard evidence for these early supercontinents is

long gone. But every 500 million years

or so geologists have spotted signs of mountain building episodes, as the

individual landmasses came together.

Mountain building is happening today in various places. The most spectacular is the

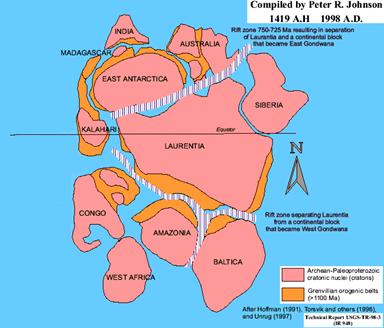

Rodinia

This

is the ancient supercontinent of Rodinia, which came together around 1100

million years ago. It’s the earliest for

which there’s any hard evidence. To be

honest, there seems to be only just enough to be sure that it actually

existed.

This

is the ancient supercontinent of Rodinia, which came together around 1100

million years ago. It’s the earliest for

which there’s any hard evidence. To be

honest, there seems to be only just enough to be sure that it actually

existed.

It was the late Proterozoic when life was still

entirely microscopic – and of course very much all underwater.

The orange patches are mountain-building areas, and the hatched areas are where there are

signs of rifting. As we keep saying,

don’t expect things to be simple in this game.

The rest of the maps all come from Christopher R.

Scotese’s Paleo mapping project (www.scotese.com).

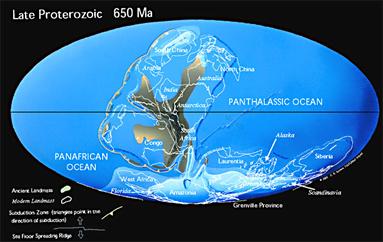

Panotia

This

is the very late Proterozoic when,

according to Scotese, a new supercontinent was being formed called Pan(n)otia

(I’ve seen it spelled both ways). It’s

the first I’d heard of it, and a report in New

Scientist (20.10.07) suggests that Panotia only ever comprised part of the

total land anyway.

This

is the very late Proterozoic when,

according to Scotese, a new supercontinent was being formed called Pan(n)otia

(I’ve seen it spelled both ways). It’s

the first I’d heard of it, and a report in New

Scientist (20.10.07) suggests that Panotia only ever comprised part of the

total land anyway.

Apparently it was complete around 550 million years

ago. However instead of going on to join

the rest of the land to produce a proper supercontinent, it seems to have

broken up again during the Cambrian (as we’ll see).

The very late Proterozoic is also the time of the

terrible Varangerian ice age. Signs of glaciation have been found on almost every continent.

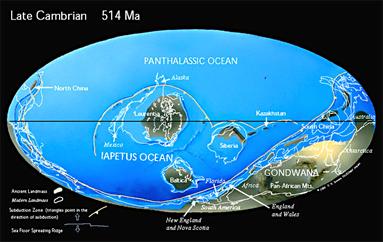

Cambrian

This is the world around the time of the great

Cambrian explosion (more) around 500

million years ago. That was when large

creatures suddenly appeared on the scene, apparently out of nowhere.

Panotia was well on the way to breaking up.

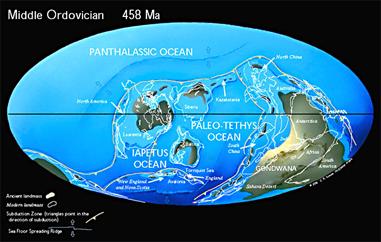

Ordovician

This is the Ordovician Period 460 million years

ago. Not a lot happens on the plate

tectonics front in a mere 40 million years – although maybe the landmasses are

beginning to get a little closer again.

Note the external ocean (more).

It’s the same as today’s Pacific, rechristened as the Panthalassa Ocean.

The mid Ordovician is the time of the Great

Diversification, when sea-floor-dwelling filter feeders exploded into the

greatest diversification of all time (more). Shortly after, round about the late

Ordovician, the plants invaded the land.

It was also one of the coldest times in Earth history, unless you

believe the full blown ‘Snowball Earth’ theory (more).

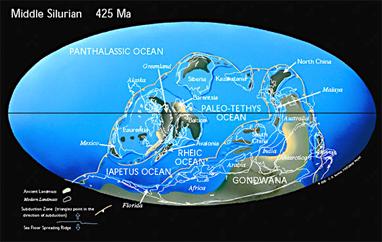

Silurian

This is the middle Silurian, 435 million years

ago. There are now definite signs that

the next supercontinent, Pangaea, is beginning to build.

Not shown on this map are the increasing areas of

shallow sea around the margins of the continents (I got this from another

map). I’ve read that this is what you

would expect at this stage.

It is around the time that the animals invaded the

land. High sea levels would be just what

was needed to give them a leg up!

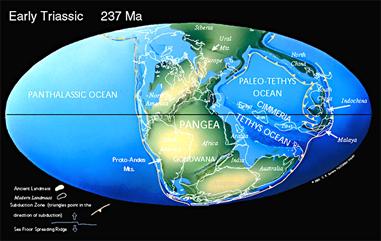

Pangaea

We

have a bigger gap here. This is the time

of the great supercontinent of Pangaea.

We

have a bigger gap here. This is the time

of the great supercontinent of Pangaea.

The amount of shallow sea has dropped, as the

sea-floor gets old and cold. The

Pacific/Panthalassa Ocean is of course still there. And we still have one large internal ocean, the

Tethys Sea.

These were hard times.

The large land mass generated widespread deserts, and the oxygen level

fell.

Shortly before this had come one of the greatest mass

extinctions of all time, the P-T event (more).

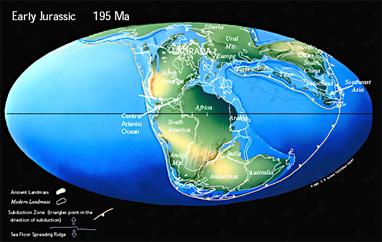

Jurassic

This is the early Jurassic. We can see that Pangaea is beginning to break

up.

The climate was much warmer than today, and stayed so

until the K-T extinction that killed off (most of)

the dinosaurs.

The early Jurassic was the start of the dinosaurs’

heyday – shortly after the Triassic extinction had killed off most of the

competition. Primitive mammals found a

niche for themselves too, but it was a pretty insignificant one.

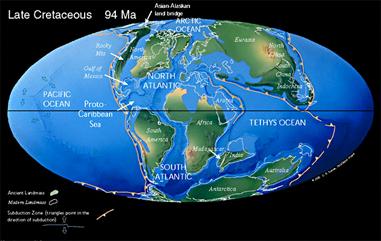

Cretaceous

This is the late Cretaceous. The break-up of Pangaea is complete. The Atlantic Ocean is beginning to open up,

and the map is beginning to look recognisable.

The Cretaceous climate was still balmy, right up to

the poles. Dinosaurs and palm trees

lived in both polar regions.

Sea level was 100-200 metres higher than today, which

created plenty of shallow seas as the continental margins were flooded. They provided plenty of channels whereby warm

water could be transported towards the poles.

Today

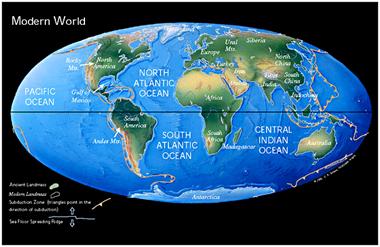

This

is today’s map. The Atlantic Ocean is

still growing at the moment. But fairly

soon (in geological terms) it will start to shrink again. It will develop its own ‘ring of fire’, as

the old tired ocean floor starts to get pushed under the continental crust (more).

This

is today’s map. The Atlantic Ocean is

still growing at the moment. But fairly

soon (in geological terms) it will start to shrink again. It will develop its own ‘ring of fire’, as

the old tired ocean floor starts to get pushed under the continental crust (more).

The past 60 million years or so have been a period of

fairly frenetic continental collision and mountain-building. India hit Asia. Spain hit France. Italy hit

France & Switzerland. Greece and

Turkey hit the Balkan region. Arabia hit Iran and Australia hit Indonesia. Together these collisions finally

extinguished the once-great Tethys Ocean.

Next

supercontinent

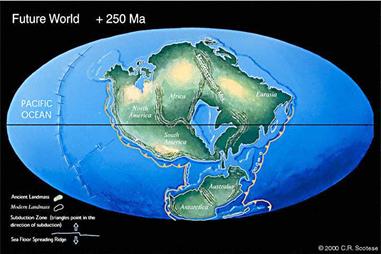

And this is the world predicted for 250 million years

hence. It represents the final stages of

the building of the next supercontinent – or possibly the early stages of its

break-up. Australia/Antarctica are

still/again separate from the main land mass.

The north Atlantic has closed up again, though in a

different way from the past. In

particular Britain and Scandinavia have drifted north, and joined northern

Russia on the edge of the Pacific (or possibly the Arctic/Pacific) Ocean. The south Atlantic has become a large inland

sea and India and south-east Asia join up.

How do they

know?

The main weapon in the palaeo-mapper’s armoury is

‘palaeo-magnetism’.

Most if not all rocks are very slightly magnetic. They contain minute specks of iron oxide, and

these act like little compasses. (If

this reminds you of magnetic tape or computer media then full marks. But don’t push the comparison too far.)

If the rock should get melted then these little

compasses are free to align themselves with the Earth’s magnetic field – just

like your hiking compass does (not quite actually as we’ll see). When the rock solidifies again these little

compasses get locked in position. They

provide a recording of where North was at the time of solidification. This recording is permanent. The Earth’s field is far too weak to

overwrite it, unless the rock should get re-melted.

Something else important happens at the same

time. The atomic clock gets reset (more). This

means that the mappers also have the date on which the ‘recording’ was

taken.

Equally important, the recordings tell the mappers the

latitude of the place where the recording was taken.

It works like this.

An ordinary compass pretends that the Earth’s field runs along the

ground. But it only actually does this

near the Equator. Everywhere else it

dips downwards. And the further north or

south you are, the greater the angle of ‘dip’.

At the poles, the field dips straight down vertically, and an ordinary

compass is useless.

An ordinary compass only measures the ‘horizontal

component’ of the Earth’s field, because that’s what most of us want. Its dial is supported on a single pin

bearing. It you put the compass on its

side the dial slips off. But you can also get ‘dip’ compasses. Their dials are properly supported like a

bicycle wheel. You can put them on

their sides and measure the ‘vertical component’, or the angle of dip. With these you can work out your latitude

without bothering with a map. Likewise

the angle of dip, as recorded by a rock sample, tells the geologists what the

latitude was when the sample last solidified.

Any large land mass will have many sites where the

rock has suffered re-melting, and made its recordings. Hopefully the recordings will cover a wide

range of dates. This enables the mappers

to plot the movement of the land mass, north and south. If the recordings are reasonably dispersed,

then the mappers can also plot the rotation of the land mass as it waltzes

about the globe.

Unfortunately there’s no such simple tool for

measuring movement east and west.

Getting a handle on this involves detailed detective work and much trial

and error.

However the geologists can often tell when landmasses

came together and split apart and this helps a great deal. For example, if they find a geological

structure in Antarctica that is identical to one they’ve already seen in Canada

(I think I have the example right) then they must once have been adjoined. With any luck, they can also estimate when

this was.

But that’s not all.

The palaeontologists can often identify fossils that are identical on

parts of two widely-separated masses.

They must once have been adjoined too.

And again the palaeontolgists can often estimate when this was.

It has taken many decades for Scotese to come up with

his definitive maps. And not all

palaeo-mappers agree with him even now.

© C B Pease, January 08