A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

History of Medicine

There’s increasing evidence that the

Egyptians were into serious medicine nearly two thousand years before the

Greeks who were supposed to have invented it.

Ancient Egyptian medicine turns out to have been remarkably similar to

modern medicine. Indeed, so advanced

were the Egyptian doctors, that we have to put the origins of modern medicine

hundreds or even thousands of years earlier still.

The origins of

modern medicine

For my part, I see no reason why the ‘spear throwers’ and the ‘Butchers of Boxgrove’

shouldn’t have been in at the beginning of medicine. They were Homo

heidelbergensis, and they were living the Life of Riley, around Heidelberg

and the south coast of England, nearly half a million years ago.

Or why not the Mighty Hunter (Homo erectus) of at least a million years earlier? Despite what some scientists may say, these

guys were already pretty smart. Their

babies were born as helpless as ours are.

So they will have needed stable communities, just like we do, to bring

their kids up safely. Some authorities

reckon that they had fire. Others reckon

that they had ‘language’. (The linguists

get upset if we use the term ‘language’ for such ancient peoples. Perhaps we should call it ‘communication’

instead. It comes to much the same

thing.) With all that going for them,

how could they not have discovered the value of at least a few herbs?

With tongue-in-cheek we can go back even

further. We read that many animals know

which herbs to eat when they are feeling rough. We can imagine our earliest forebears being at

least as knowledgeable as these animals.

As time passed, and their brains grew, they

will surely have started to expand this ‘instinctive’ knowledge into the first

glimmerings of a medical practice. When

might this have been? We’ll probably

never know.

We’re talking about herbal medicine to be

sure. But until the discovery of

antibiotics, which was well into my lifetime, herbal products were the basis of

much of our medicine too. Perhaps they

still are. I remember a retired GP

saying that he used to keep four large bottles of medicines on a shelf in his

surgery. If the first one didn’t help

the patient, then one of the others probably would. Pharmacists didn’t tell you what was in your

medicine in those days, which was just as well.

These four bottles simply contained different coloured suspensions of

aspirin. And what is aspirin? Artificial willow bark!

Even today, biologists are scouring the

tropical rain forests, looking for new drugs that might be useful to us humans

(more).

Ancient Egyptian medicine

Perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us that the

ancients homed in on much the same medicines as we did, for two reasons. First, as we keep having to point out,

ancient folk were smart too. Second, the

ailments will have been the same, and so will the properties of the herbs.

I make no claim that this piece is either

comprehensive or authoritative. But,

according to New Scientist (15.12.07),

Jackie Campbell of the

Historians know all about ancient Greek

medicine, because they wrote huge amounts – and all in plain Greek.

By contrast, the Egyptians did what modern

medicos did until recently, only worse.

They wrote in their own private language, that even scholars are  having great difficulty with.

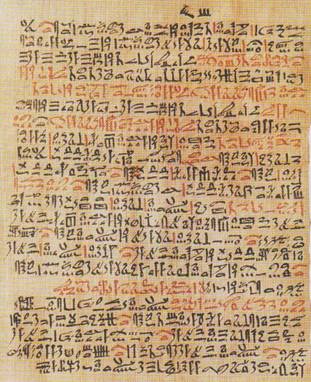

This is an example, taken from the N.S.

article. It’s part of a papyrus from

about 3˝ thousand years ago (1500 BC).

It contains 877 prescriptions. By

this time Egyptian medicine was already very sophisticated. It must have taken their doctors a long time

to home in on such high quality, by pure trial end error. So, as we’ve already suggested, it roots must

have gone back a long way.

having great difficulty with.

This is an example, taken from the N.S.

article. It’s part of a papyrus from

about 3˝ thousand years ago (1500 BC).

It contains 877 prescriptions. By

this time Egyptian medicine was already very sophisticated. It must have taken their doctors a long time

to home in on such high quality, by pure trial end error. So, as we’ve already suggested, it roots must

have gone back a long way.

Linguists have been making heroic efforts to

translate papyri like this one for over a hundred years. But the normal code-breaking strategies don’t

work on simple lists of ingredients. And

the ingredients list is the most vital part of any prescription.

As a result, over 30% of the linguists’ ‘educated

guesses’ are disputed. This is far too

many errors for the results to be of much use to anybody else. We engineers would cancel a project if we

couldn’t find a way of getting much better initial data than that.

Fortunately,

Further research will reveal how accurate

Campbell’s results are. But the New scientist thought the story well

worth an airing. And that’s good enough

for me.

Campbell started by investigating which

plants grew, or were traded, at the time.

Fortunately the flora of ancient Egypt is well known. And this enabled her to rule out a number of

the linguists’ guesses. For example,

cinnamon and aniseed were both cited, but it’s almost certain that neither was

available to the doctors of the time.

Next she looked at the recipes

themselves. Quite apart from not being

available, cinnamon and aniseed don’t do what the translated recipe says

anyway. Other ingredients were clearly

wrong too.

However many of the recipes were spot

on. First, the active drug was to be

extracted in a way that works. There’s

often only one way to do this. The

active ingredient in the bitter apple (a powerful laxative) can only be

obtained by steeping the fruit in mild alcohol.

That’s how it’s done today, and that’s how the Egyptians did it. Others need a two stage process, first in

water or alcohol, and then in acid. The

Egyptians did it this way, and so do we.

Some herbs need boiling and others

need grinding up first, and so on. We

know this and so did the Egyptians.

Second, the formulation did what the

recipe said it did. Campbell found that

67% of her Egyptian remedies complied with the ‘1973 British Pharmaceutical

Codex’. This is the bible that, until

very recently, told pharmacists which medicines to make up for which ailment –

and how to do it. The only proviso is

that the Egyptians knew nothing about the need for sterility.

Third, the drug was given ‘the right way’

(arrogant lot aren’t we these days). The

Egyptians couldn’t inject their drugs.

But they had virtually all the other techniques available to modern

doctors, from eye drops and inhalers to enemas and suppositories.

Fourth, in many cases even the dosage was

‘right’. Not always though. Often the dose seemed too small to be

effective. There’s an explanation for

this. Plants don’t produce these poisons

for fun. They do it, at considerable

‘cost’ to themselves, to fight off diseases and predators. The wild herbs that the Egyptians used were

still under attack. So they had to keep

their defences up. Modern cultivated

varieties are generally grown in a much more benign environment. So they could have lost a lot of their

potency down the centuries.

On the other hand the Egyptians knew

little about the causes of disease. So

their medicine concentrated on alleviating symptoms. We shouldn’t belittle them for this though. Much of modern medicine is the same.

The Egyptians may not have known anything

about infection, but they did know that resins and metals helped healing. We now know that both of these are toxic to

bugs. Their treatment of wounds was

clearly effective. Many mummies show

signs of potentially fatal wounds – which had instead healed. They also treated their wounds with

honey. Don’t laugh. Honey is coming back into favour as

antibiotics increasingly fail. Its

effect is to dry the wound out so much that bacteria can’t grow.

Not all their remedies were effective

though. Their cure for impotence comprised

39 different ingredients, not one of which would have had the slightest

effect. However we mustn’t forget the

placebo effect, which is still a major part of medicine today. Their contraceptives might have worked. One was animal dung which is acid. It might have been effective if inserted as a

suppository. Somehow I can’t see us

checking that one out!

All in all we could have done a lot worse

than to have lived in ancient Egyptian times, if we had money that is. But there are plenty of countries today where

lack of money denies you access to medical care.

©C B Pease, January 08