A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

Supercontinents

When I was young we were fascinated by the mysterious

ancient supercontinent of Gondwanaland. It existed way back in the mists of time, when

the world was young and the dinosaurs were King.

Geological and Biological

timescales Early supercontinents Effect on climate Continental Cycle

Later we learned that Gondwanaland was small beer,

comprising only about half the planet’s land area (basically today’s southern

hemisphere). The rest of the land

resided in other equally large landmasses, with names such as Laurentia and

Even more disappointing, it was all relatively

recent. The real supercontinent, that

really was around when the world was young, was Pangaea. And Pangaea really did comprise virtually all

the planet’s land, and the dinosaurs had yet

to appear.

Now we know that even Pangaea was no more than

‘yesterday’ in the life of our planet.

The dinosaurs may be yet to come, but a great deal had already happened

on the ‘life’ front.

Geological and Biological timescales

However before we go any further, we’ll consider the

difference between geological and biological timescales. It’s important because the geological time

scale is far longer than the biological timescale.

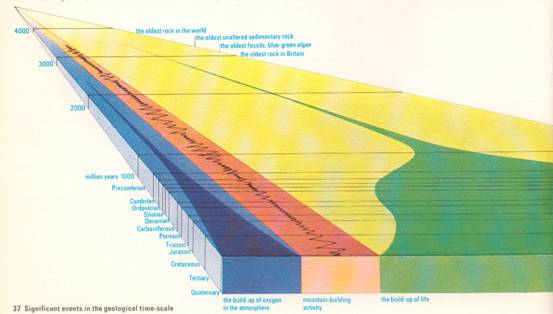

This diagram comes from a Geological  Museum

booklet from 1981. The main part shows

the explosive build up of life from about 1000 million years ago. The red strip shows episodes of mountain

building. These are caused by land masses

crashing together, and indicate a supercontinent in the making. The blue strip shows how, at the time, they

thought the build-up of atmospheric oxygen was going. In fact the oxygen issue is still

controversial today.

Museum

booklet from 1981. The main part shows

the explosive build up of life from about 1000 million years ago. The red strip shows episodes of mountain

building. These are caused by land masses

crashing together, and indicate a supercontinent in the making. The blue strip shows how, at the time, they

thought the build-up of atmospheric oxygen was going. In fact the oxygen issue is still

controversial today.

Five hundred

million years ago, life had only just discovered the ‘big is beautiful’

concept, with the Ediacara fauna followed

closely by the Great Cambrian explosion. Animals, trees, giant dragonflies and so on,

were all still to come. Let alone

dinosaurs, birds and mammals. Before

around 500 million years ago, even ‘advanced’ life existed only on a

microscopic scale.

And advanced life of any kind existed entirely

underwater. The dry land was either

completely bare, or ruled by organisms such as bacteria and algae.

But on a geological timescale, 500 million years is

nothing. Geologists can produce chapter

and verse of how, for example, the Atlantic Ocean has opened and closed several

times – at around 500 million years a throw.

Incidentally, each time it opened up, Scotland found itself with another

chunk added on. The Great Glen (Loch

Ness etc.) is only the latest of the geological ‘faults’ that show this.

(The truth is actually a good deal more complicated

than I’ve just made out. The continents

were doing a stately dance around each other, under the influence of plate tectonics. So the continents on the other side of the

‘Atlantic’ weren’t always the same. And

geologists give the Atlantic’s previous incarnations different names. But if you don’t want to get bogged down in

detail, it’s perfectly reasonable just to remember the simple story.)

The continental cycle

The most recent supercontinent is Pangaea, which

lasted from about 250 to 150 million years ago.

That’s from shortly before the dinosaurs appeared to the middle of their

heyday.

There was an even earlier supercontinent called

Rodinia. Not surprisingly, there’s much

less known about Rodinia. But it seems

to have existed around 1100 million

years ago. This was somewhere around the

time of the terrible Varangerian ice age.

However, as the diagram suggests, geologists now

believe that there’s a coming together of land masses every 500 million years

or so. They stay together for about 100

million years and then they break apart again.

How do they know?

Well you won’t be too surprised to learn that, as the landmasses come

together, there’s a spate of mountain building – as is happening today before

our eyes. India is slamming against

Asia, burying itself underneath, and pushing up the Himalayas.

Incidentally we mustn’t confuse this kind of mountain

building with what is going on all around the Pacific. If there are volcanoes then we have oceanic crust burying itself more.

There are no volcanoes in the

Likewise, as the landmasses are split apart, there’s a

spate of ‘rifting’. Again we’re

lucky. There’s an example of that too,

in Africa’s Great Rift Valley. In 100

million year’s time there may be an ocean separating East Africa off from the

rest.

The evidence for earlier supercontinents tenuous, but

convincing to geologists. They have

detected signs of a worldwide spate of this mountain building – followed a

hundred million years later by a worldwide spate of rifting. And, as we’ve mentioned, these episodes seem

to have happened roughly every 500 million years.

Early supercontinents

It seems unlikely that the earlier episodes succeeded

in assembling all the land into single supercontinents. Large land masses are a sign that the plate

tectonics process is beginning to get tired.

The land probably assembled into large islands, and then broke apart

again into smaller ones.

Effect on climate

The state of the supercontinent cycle has a huge

effect on the climate, the constitution of the atmosphere and even on the

amount of land there is (Click here for

more on sea levels). It’s extremely complicated, and we can’t

afford to go into it. However several

mass extinctions have been attributed to the stage of the supercontinent cycle.

© C B Pease, February 08