A TIMELINE FOR THE PLANET click for Home Page

The Ediacara

fauna

The Ediacarans were life’s first experiment in

large-scale living – or so it was believed for a long time. We now know that algae had beaten them to it,

in the form of seaweeds.

The Ediacarans are classed as animals, although it’s

not too clear why. They had none of the

internal structure that we associate with animals. The experiment ultimately failed. Few if any creatures from life’s next stage

appear to have descended from the Ediacarans.

So

these fossils are the oldest large-sized examples known. They stem from the late Precambrian, which

had never yielded up fossils of any kind before (more).

In fact the late Precambrian rocks were teeming with fossils. But they were all microscopic, and nobody was

using microscopes to look for fossils at the time (more).

The first Ediacarans were found in the 1940s, in the Ediacara Hills of

So

these fossils are the oldest large-sized examples known. They stem from the late Precambrian, which

had never yielded up fossils of any kind before (more).

In fact the late Precambrian rocks were teeming with fossils. But they were all microscopic, and nobody was

using microscopes to look for fossils at the time (more).

The first Ediacarans were found in the 1940s, in the Ediacara Hills of

The Ediacara creatures had no hard

parts, so most of them rotted completely away as soon as they died. But occasionally an underwater mud slide will

despatch an entire zone of living organisms – and preserve them for

posterity. And we have a few of these

to thank for knowing that these strange creatures ever existed. (See also the Burgess

Shale). And once palaeontologists knew where to look,

they began to turn up in various places around the world.

The Ediacara creatures were quite unlike anything that

scientists had seen before. So it’s not

surprising that it took a while for scientists to make sense of them. The story changed quite a bit over the years.

But a recent article in New scientist (14 Apr. 07) reckons that they’ve now  been

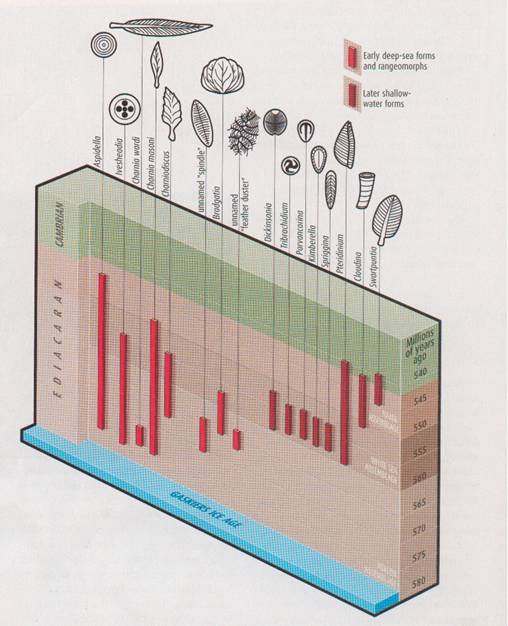

sorted. This drawing of how the

Ediacarans might have looked comes from the article. It seems that they came in two quite separate

groups, one after the other (so to speak).

been

sorted. This drawing of how the

Ediacarans might have looked comes from the article. It seems that they came in two quite separate

groups, one after the other (so to speak).

The first group were the rangeomorphs. They

emerged about 575 million years ago.

This was just 5 million years after the end of the terrible Varangarian ice age. (The N.S.

calls it ‘the Gaskiers’, but I’m sticking with Varangarian for the time

being.) They inhabited exclusively the

deep sea bed. They lasted for 15 million

years, and then slowly died out leaving no issue.

The rangeomorphs came in various sizes. Most would fit

comfortably into a shoe box, but the largest were over 4 metres long. On the face of it, this is ridiculous. Everything, but everything, that had gone

before was microscopic.  And

now all of a sudden, we have these huge creatures appearing out of

nowhere. How was this possible?

And

now all of a sudden, we have these huge creatures appearing out of

nowhere. How was this possible?

The theory goes like this. In the aftermath of the ice age, even the

deep oceans became heavily oxygenated.

In addition, the oceans will have been bursting with organic matter,

released by the melting glaciers. So all

a creature had to do was to stand there with its mouth open, and food would

pour in. In fact the Ediacarans didn’t

have mouths. They absorbed the nutrients

through their surfaces. This meant that

the bigger you were, the better.

I don’t pretend to understand the following. But apparently the rangeomorphs were able to

grow big quite so fast because they had a ‘fractal’ design.

However after 15 million years conditions

changed. Either the supply of free food

dried up or the competition for it became too fierce. And the rangeomorphs had no answer. The last rangeomorph disappears from the

fossil record about 545 million years ago.

However, about 560 million years ago, a new breed

appeared, this time occupying the shallow waters. The arrival of the shallow-water Ediacarans

led to a golden age, with bio diversity reaching a peak for 10 million years. Most of them have no clear link to the Cambrian animals that came immediately

afterwards. But it seems that a few went

on to spawn genuine Cambrian creatures, and thus continue their line.

There are tantalising hints that some of the shallow-water

Ediacarans were remarkably jellyfish like.

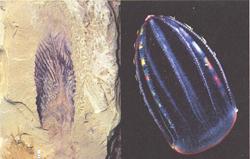

Now a creature has been found, from well within the Cambrian period (151

million years to be precise) which palaeontologists think was a true descendent

of one of these. They’ve called it Stromatoveris. It’s the fossil on the left, which comes from

New Scientist 13 May 06. The picture on the right is of a modern ‘comb

jelly’, and it’s thought that the entire phylum of comb jellies (ctenophores) are direct

descendents of this little lad, Stromatoveris.

The fossil record

The fossil record

This creature has filled in an important gap in the fossil record.

Until it was found, there seemed to be a complete break between the

mysterious Ediacara fauna and the trilobites and others of the Cambrian

period. It was if there had been an

almost total mass extinction between the two periods. Now we can see that some creatures at least

lived through any upheavals there may have been. Indeed there may well have been no extinction

at all – just this gap in the record.

© C B Pease, December 07